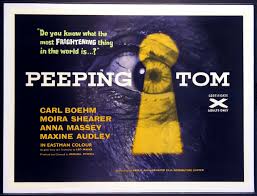

Peeping Tom (1960)

Dir. Michael Powell

Written by Leo Marks

Starring Carl Boehm, Anna Massey, Moira Shearer, Maxine Audley

Well, if you’re going to have your career ruined, this is the way to do it. PEEPING TOM is something of a masterpiece, a deeply disquieting and astonishingly psychologically complex proto-slasher, totally unlike anything that came before it. It’s nuanced, tense, and subtly remarkable in it’s filmmaking. It features a main character almost completely unique in the history of cinema. It is, frankly, rather brilliant. And it was so widely reviled when it premiered that director Michael Powell’s (THE LIFE AND DEATH OF COLONEL BLIMP) career was basically ruined, and he would not find work as a director in his native England for well over a decade. I hope Powell eventually sent Criterion editions of his movie to all those critics who fucked him over back then.

The title PEEPING TOM suggests something pretty sleazy, and the way the murders occur --the victim being filmed while they’re stabbed with a bladed tripod foot from the camera-- is certainly a prurient enough gimmick for any self-respecting exploitation film to feel confident with. And wait til I tell you that our titular character has a side gig as a photographer for a softcore nudie ring run out of the attic of a shady corner-store news shop. Sounds pretty Italian, if you get my drift. But it doesn’t play out that way, exactly. Though I’m sure this was all jarringly perverse back in 1960, there’s very little here which seems interested in titillating. Instead, the movie is interested in intimacy -- whether that intimacy is due to sexual attraction, familial bonds, or horrific death -- and what happens when that intimacy is mediated --dare we say violated?-- by a camera.

See, our nominal hero Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm, various movie Nazis), is a quiet, shy boy, who lives in the apartment in which he grew up with his prominent psychologist father (now deceased). He’s obsessed with filming everything --he has a small camera hidden in his coat pocket which he keeps running nearly all the time -- because, it seems, his own childhood was defined by being watched. His father filmed him relentlessly, subjecting him to torments from throwing lizards onto his bed while he slept to filming his reaction to his mother’s corpse (and, it’s lightly suggested, some even darker scenarios) in the hopes of gathering data about the human fear response. And yet, intriguingly, it’s not fear that interests his son, exactly; it’s the camera itself, the process of watching, of capturing a part of someone forever on film. That’s why he’s a Peeping Tom, not just a Killing Tom, though he’s that too. Those he films have bad ends coming their way, which makes it a real problem when the girl next door (well, technically the girl one floor below) decides to bring him out of his shell, and he finds he genuinely likes her.

For a perverted serial killer, Mark is portrayed surprisingly sympathetically. Boehm gives him a timid, bashful manner --complimented with his striking, haunted blue eyes, always fixed in an anguished thousand-yard stare-- and really gives us a sense of how horrible this guy’s inner life must be. I don’t think he smiles once the whole way through; the fact that he’s moved from being an unwilling subject for the camera to the director behind it hasn’t brought him any comfort, or even any increased feelings of control -- he’s still just a part of the horrifying experiment which has been his life, he can’t escape from it even with his father gone. His miserable childhood never ended: it's crystallized, perfectly preserved in those films which are bound to repeat endlessly, just like his memories and just like his behaviors. That doesn’t make him any less terrifying; in fact, if anything, it makes him scarier, because he doesn’t even want to be doing this, he just can’t help himself. It makes his nice guy routine all the easier to buy, because it’s true, he’s not putting on an act. He is a nice guy, just one who has to murder women while filming them from time to time. The poor little girl from downstairs has no idea what she’s getting into.

One person who may actually have a better idea is her blind, alcoholic mother (Maxine Audley, Chaplin’s A KING IN NEW YORK, FRANKENSTEIN MUST BE DESTROYED), who has lived downstairs from Mark and his father since she was a child, and claims to have been listening to their feet upstairs all that time. She has an intriguing scene where she confronts Mark in his inner sanctum -- his screening room, where he endlessly watches repeated reels of his own stolen childhood intermingled with the visions of the murders he’s committed -- and has a fraught but ambiguous conversation with him about his obsession with filming. She’s blind, so she can’t see that while they’re talking, he’s silently projecting murder footage onto her, but even so she seems completely in control of the situation, intimating that she knows more than she’s saying. But if so, why doesn’t she go to the police? Does she feel sorry for the lad, knowing the unending hell he endured? Does she, a blind woman, perhaps not understand the terrible compelling power of images, and misjudges his compulsion? Is it, perhaps, that she has her own demons which have turned her into her own kind of monster over the years, and can’t bring herself to judge him? You can read a lot into Audley’s terrific performance, but the answers are are just as elusive as the performance is provocative.

In fact, there is quite a bounty of curious, meticulously cultivated and suggestive details here which are never explicitly resolved. We know enough to understand the psychological mechanics of the narrative, but Powell expertly leaves things open-ended enough that ghostly tendrils of other -- perhaps even darker-- possibilities seem to lurk at the edges of the frame. The murders themselves are relatively bloodless affairs, even by the then-contemporary standards of the equally shocking PSYCHO which premiered a few months later. But the twisted mind and the twisted history behind them still have the power to greatly disturb, more than half a century later. Powell’s moody direction is part of that, but you also have to give enormous credit to the revolutionary and highly literate script by English cryptographer-turned-screenwriter Leo Marks, who crafted a script with a sadistic genius for casually dropping little morsels of detail which open up whole worlds of frightening possibilities (Martin Scorsese, recognizing the obvious evil here, had Marks voice the devil in his LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST). Between the two of them, there’s something feverish and profoundly disconcerting about the experience that has less to do with violence and more to do with its brazen ability to look directly into a truly disturbed mind without flinching, or over explaining. The result is an unabashed classic of the horror genre, and a crushing refutation of anyone who would ever claim that horror can’t be great art.

*****************************Overture****************************

The film as a whole looks great; it’s mostly unflashy by today’s standards, but Powell crafts some splendidly composed images, full of evocative lighting and punctuated by an interesting color palette. The real innovation here, though --the one which unquestionably changed horror forever, if not film in general -- is his use of the killer’s perspective. The film begins looking through the killer’s camera eye. Long before we see the face of our hero/villain, we’re walking in his shoes, stalking one of of London’s suspiciously clean-looking working girls and watching her scream in horror as she realizes she’s about to die. It’s a very unsettling experience, refusing to let the viewer be a passive witness to this horrible scene but at the same time giving us no control over “our” actions. This makes it a particularly fitting use of this trope, since of course that’s how Mark feels anyway; a helpless puppet, forced into these grim routines by forces beyond his control.

The killer’s-point-of-view is not something exclusive to horror movies, but I think it’s hardly controversial to say that the horror genre has made the most use of this intriguing gimmick. Powell didn’t invent POV camerawork, of course; I can find examples at least as far back as 1927’s NAPOLEON, and I suspect there are even older examples as well. After all, cinema as an art form in inherently an expression of a particular point-of-view (the camera’s) and the language of cinema quickly developed to reflect its ability to present the unique subjective perspective of participants in the story. Anytime we see a character notice something, and then cut to a shot of whatever it is he or she is observing, we are assuming the camera represents something akin to the character’s perspective. But Powell may well have noticed something in it that no one else had before. Imprisoning us in the body of a killer as he murders screaming young women is indeed a nauseating experience, a protracted nightmare in which you’re horrified at what you’re doing, but powerless to stop yourself.

It’s a visceral, troubling sequence on it’s own, but It’s also clear that Powell has more on his mind than simple shock tactics. This is not just a killer’s perspective, it’s very consciously a camera’s perspective; the camera is a constant mediator between him and the world, just as it is between us and his world. We’re united with the killer in our inquisitive interest as an audience, even if what we see repels us. We later see the same footage the film began with, now projected onto a screen and being watched intently by our protagonist, and consequently by us as well. Not only are we complicit in creating the horrors of this scene, we’re sitting in a theater with the killer, re-living it! And of course, while he’s watching the film of her, we’re also watching film footage of him.

This nifty little meta trick on Powell’s part bring into sharp focus the degree to which cinema itself is inherently somewhat of a voyeuristic medium. This will be our theme this year, for the auspicious CHAINSAWNUKAH 2015: PLAY IT AGAIN, SAMHAIN. Since the dawn of cinema, we, like our titular Peeping Tom, have been sitting in the dark, peering into other people’s lives without their knowledge or consent. Now of course, this is a little different than peering into people’s windows, because of course the people in the film are actors who are tacitly acknowledging that they want us to watch them, even when they’re doing things which appear somewhat vulnerable or compromising -- just like, incidentally, the nudie models that Mark Lewis photographs. But even so, there’s something inherently rather seedy in that power dynamic. The person watching has all the power, and nothing at stake except our voyeuristic curiosity. And that voyeuristic desire is something everyone possesses, often just as strongly as the paradoxical desire to not be spied upon ourselves, Everyone wants to watch, but no one really want to be watched, especially without their knowledge. Inevitably, the people behind the camera are the ones in control, and the subject of the camera eye is at their mercy.

The genius of PEEPING TOM is that its unusual structure forces the viewer into the uncomfortable position of being disturbed by the very action in which we’re also partaking (well, minus the active murder), and yet making the viewer such an active participant and such an obvious parallel to the protagonist that there’s no way of escaping our synchronicity of purpose. The movie forces us to not just passively observe what Mark Lewis does, but to actively participate with him both in the murders (through our shared perspective) and in the act of watching those murders (as we see re-experience those events while both he and we watch them on film). Just in case you had any doubt that this was the movie’s intention, note that Powell himself plays Lewis’s father in a silent bit of old footage which finds him, for just a few seconds, walking out from behind the camera. A psychologist who meets the younger Lewis muses, “He has his father’s eyes…” Powell, the director, has orchestrated all this horror; but it is his cinematic creation, his fictional son, who will act it out, and it has all been done for us, the silent audience, grinning and egging him on (well, actually not at the time, when it was widely despised. But the idea is there).

PEEPING TOM makes explicit the perverse titillation of watching fictional depravity play out for our amusement, but the concept reaches far deeper into the horror genre than the meta-commentary on display here. Consider, of course, the many giallos and American slashers which feature the famous “Killer’s Point-of-View” shots. From the many murders we witness through the killer’s mask (for example, the first scene in HALLOWEEN) to the invisible, roving camera in THE EVIL DEAD, to the stalking, unseen horrors of many a 50’s monster movie, horror cinema uniquely of all genres is replete with subjective perspectives from killers, monsters, demons, predators, and even the rogue flying skull or two. Often, there will be distinct characteristics of the subjective point of view to visually differentiate the decidedly non-human perspective of our unseen monster (the heat-vision in PREDATOR, or the strange inverted color of the wolves’ vision in WOLFEN) but the fundamental mechanics of the horror remain the same: malevolent danger, whether seen or unseen, is watching our characters. We know they’re being watched, we understand the moral peril they’re in, but only too late will they realize it. Again, the watcher holds all the power; their victim is left only to react, and even then, only when the watcher chooses to reveal his or her presence. While sometimes our killer’s POV is used to heighten the horror of the victim and establish an intimacy as he or she meets our eyes at the very peak moment of terror (and also to avoid depicting a costly monster puppet), more often this perspective is the purview of the hunter, the stealthy predator slowly but steadily drawing closer to its prey, which is painfully, achingly unaware of the violent death drawing inexorably closer.

|

| Killer's blurry POV in 1981's THE BURNING... |

|

| ...Through the eyeholes of a mask in HALLOWEEN (1978)... |

|

| ...And from the perspective of a murderous crawling eye, in uh, THE CRAWLING EYE, 1958. |

It is this slowly clenching dread which is at the heart of tension and horror, of course. Hitchcock famously pointed out that the difference between surprise and suspense is all in the audience’s knowledge of the approaching peril: a bomb hidden under a table which suddenly explodes may shock the viewers, but a bomb sitting silently, observed only by us, quietly ticking away towards that moment of violence -- that is suspense, our dawning understanding of the stakes, and our escalating agitation that the characters don’t know what they’re up against yet. Hitchcock tellingly describes the situation thusly:

“In these conditions, [an] innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: ‘You shouldn't be talking about such trivial matters. There is a bomb beneath you and it is about to explode!’” [emphasis mine]

That participation he describes is, I think, the key to understanding the reason voyeurism is so deeply embedded in the heart of the horror genre. The deeper we go into the subjective perspectives of our characters, the more directly we’re participants in the action, not mere observers. It explains, to some extent, the enormous proliferation of the found-footage genre in recent years (well, along with their enormously reduced cost, anyway): in adopting (usually) the victim’s point-of-view, we’re intentionally limiting our perspective, intentionally relinquishing the controlling power the voyeur’s role affords us, and making ourselves vulnerable to the red-eyed nightmares watching us from somewhere out there in the dark. Of course, even when we limit our perspective to the victim, we still have something that keeps us actively participating in the drama, because we know something the character’s don’t: we know they’re in a horror movie. So it’s back to the table with the bomb under it: they may think they’re having a normal day, but we’re anxiously scanning the shadows for the hint of a danger we know is out there. In very rare occasions, we may even transition between these perspectives: in Eduardo Sanchez’s (not-all-that-great) segment of VHS 2, for example, we begin our film from the perspective of the victim, a biker who gets attacked by zombies. Halfway through, though, our protagonist is bitten and becomes a zombie himself, abruptly but seamlessly turning us from a victim’s perspective to a killer’s. The hunted becomes the hunter, and abruptly we find ourselves a stalker again, in a world full of prey.

No comments:

Post a Comment