Star Wars VII: The Force Awakens (2016)

Dir. J. Jonah Abramson

Written by J. Jonah Abramson and Lawrence Kasdan & Michael Arndt

Starring Daisy Ridley, John Boyega, Harrison Ford, Adam Driver, Oscar Isaac

Prologue: Before The Dark Time. Before the Empire.

You may not believe this, but it’s true: when I first heard that George Lucas was selling off the universe he had created and ruled like a jealous god for 35 years, I was… happy. Here’s what I had to say about it on October 20, 2012:

“Although Lucas will always be the essence of STAR WARS, I’m not too sorry it’s out of his hands now (and in his hands are a cool 4 fucking billion dollars). Honestly, Lucas had a very love-hate relationship with his own work, and I think it showed in the tortured but sporadic greatness of the prequels. He created the universe, but STAR WARS has always been a big sandbox for other people to play in, even from the very beginning. Lucas’s genius is not as a storyteller, but as a guy who imagined a place vivid enough for everyone to want to tell their own story about. As long as Disney can find the right person to tell their own story, I think it’ll ultimately be better for the series and I have no regrets….

I’m someone who genuinely thinks the prequels are unique and special, so please don’t let that come off as a “fuck Lucas”. Actually, I’m kind of happy he has that monkey off his back. Let him do his own thing, and let the amazing universe he created live on its own.”

It seemed like most people felt that way. Only wise old sage Mr. Majestyk offered any words of mourning:

“Look at it this way: Yesterday, the single largest and most successful creative endeavor ever devised by a single human mind was completely owned and controlled by the artist who created it. Like all things that don’t come off an assembly line, it was imperfect and full of charmingly human flaws. Today, it is owned and controlled by a corporation whose very name is synonymous with cultural homogenization. It will be everything you want, because customer service is their business.

I don’t know how to see this as a good thing. To me, it’s just another mom-and-pop bought out by a chain. It’s not STAR WARS anymore. It’s STAR BUCKS.“

By October 31 of the same year, though, I was still feeling good:

I do feel a twinge of sadness at the passing of the franchise from the hands of one flawed but legitimately visionary creator to a corporation. But if I may throw in a small voice of optimism, I have to say I think this is for the best right now. I simply don’t believe Lucas had any more interest in playing in the universe he created. I think it ultimately became too difficult for him to separate his artistic interest from the enormous public phenomenon that was STAR WARS. In recent years, he’s almost actively antagonistic with fans of the series. I think he honestly felt chained to it; unable to let it go but forced to pursue it only because of the insane pressure of being the head of one of the most lucrative franchises in history. No one can replace his unique insanity, but it’s almost a relief that the guy is free from it now.

And here’s the thing: STAR WARS’s greatest strength is that it has to be among the most vividly and richly imagined universes ever created. That, more than anything, explains how the universe has been expanded by so much media. EVERYONE who encounters STAR WARS wants to tell their own story about it. I mean, people liked PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN too, but no one is devoting their life to making claymation webisodes based on the adventures of Jack Sparrow. For STAR WARS, there are literally hundreds of people doing that. Maybe thousands. It’s inviting for the simple reason that this whole incredibly detailed, rich, living universe spilled out of Lucas’s crazy head into our world simply *brimming* with stories to be told. Lucas has been caught in a weird purgatory of being uncomfortable with other people playing his sandbox (just watch the fascinating and funny THE PEOPLE VS. GEORGE LUCAS for more on that dynamic) but also conflicted about wasting his whole artistic life on this one project.

Now, that conflict is resolved — George is free to do what he likes (and has 4 billion dollars to do it), and other artists are finally invited to play in his amazing world. I’m not worried that Disney will turn it into a commodity, simply because people love the world too intensely to allow that to happen. There’s a line of a hundred fantastic, passionate artists who would love to tell their STAR WARS story. And unlike Lucas, these will be people who genuinely want to tell a story. I don’t expect we’ll ever get anything as crazy and wonderful and frustrating as the Prequels were, but it almost doesn’t matter at this point. Lucas gave the world an incredible gift: A fully realized, exquisitely detailed and fully *alive* alternate reality to play in. Now, he can finally let that reality really run free and take on a life of it’s own. And there’s as many stories to tell in that reality as there are in our own. When people who genuinely, intensely love spending time there get their chance to tell those stories, I fully expect the results to be remarkable.

I mean, think about it. That kind of stunning, rich detail combined with a genuinely mythic, well-told story? Sounds like… well, the original STAR WARS.”

Time passed. Dark forces gathered. In 2013, another classic Sci-Fi series had its second big “reboot” sequel. Here’s what I had to say about that:

“Ugh, this [STAR TREK: INTO DARKNESS movie] seems to me like just more evidence that poor J.J. Abrams loves the right things, but doesn’t understand why they work. Just like SUPER 8 assembles all the correct ingredients of a Spielberg 80’s monster movie without really following through on any of them. Just like STAR TREK REBOOT fastidiously cultivates a million tiny details from the original series, while simultaneously dumping all the conflicts and philosophy which defined the series. As if what really matters in a sci-fi series is the names and accents of the main characters instead of the undergirding logic of the story. That seems to be Abram’s MO: He gathers ingredients, but he doesn’t seem to understand that then you have to cook them. And (unless your name is Quentin Tarantino) you just can’t expect to make a real movie by assembling the pieces of things you liked from other movies. You actually have to understand how those pieces worked together to actually establish some meaningful content. That’s what Abrams lacks. There’s nothing wrong with his TREK movies on the surface, they’re perfectly fun fluff (well, INTO DARKNESS is a narrative catastrophe, but so are all big-budget movies these days, so whatever). But can you seriously imagine people going to conventions and obsessing about them 30 years later? Not a chance. In fact, I heard a hilariously awkward interview with Zachary Quinto where the interviewer asked him if he was having trouble with the “Notoriously obsessive” Star Trek fans, and he just kind of said, ‘ah, no, I think people these days don’t get as deeply invested in things.’ Right, it’s people who are different, not the movies?

... PHANTOM MENACE, flawed as it obviously is, taught us that some franchises have the balls to really surprise you. Abram’s STAR TREK films are the films STAR WARS fans *thought* they wanted — superficially complicated but internally dull space fantasy which deliver re-skinned versions of the exact same things they remember from the originals, entertain and are immediately forgotten. I guess we won’t know for awhile, but I have a strong suspicion that Abrams TREK films will be long forgotten in ten years while the Prequels are still watched.

So that’s how I already felt about J. J. Abrams, when, in January 2013, I woke up to a nasty surprise. My first reaction was muted resignation:

“To me, Abrams is the epitome of lightweight, disposable pap that is workmanlike but almost instantly forgettable. There’s not a moment in his filmography that feels like the work of someone with a passion for telling stories or making movies. I’m sorry, but this is the slightly hipper equal of hiring Brett Ratner. “OK Mr. Director, we need a straightforward normal movie that won’t rock the boat and will come in under budget and on time.” The perfect way to come out with a STAR WARS film which is under-imagined and completely neutered, but will make a bag full of money for a few weeks until people move on to the next thing and forget about it.”

But, then I got a little more intense about it. On April 30, 2014, I wrote:

I could not be more cynical about this whole enterprise.

To tell you the truth, though, I was actually sort of excited when Lucas sold the franchise… but the moment they said the words “J.J. Abrams” my heart sank. Nevermind the obvious moral wrongness of putting the same guy in charge of both TREK and WARS… nevermind that the guy is a boring hack… the problem is that putting him in charge is just such a transparently corporate safe money thing to do. “This guy made that stupid nerd space series popular again, right? Those movies made money, the kids went to see them. He should be able to do the same thing with these other space movies.” Ugh. How utterly depressing. This was gonna be a creative process built around spreadsheets.

And THEN, when they explained they were bringing back the whole original cast, I knew I was done with it. How utterly lacking in even the slightest bit of imagination do you have to be to have nothing to do in this entire, huge universe but to wring a few more miles out of the characters people are already familiar with. How utterly desperate to pander do you have to be, how utterly afraid of the fans do you have to be, to get to the point where you can justify that to yourself? If there was ever a question asked even less than “I wonder what Darth Vader was like as a kid” it HAS to be “I wonder what Han was like as an old man, after he got done with his obvious character arc from the movie and defeated the Empire. How was retirement treating him? I’d really love to have an answer to that question.”

These are the moves of desperate, boring people who have too much potential money on the line to do anything even remotely interesting. And it didn’t have to be this way — it’s fuckin’ STAR WARS. It was a sure thing no matter what, you don’t have to homogenize it as much as possible to sell tickets! You didn’t have to turn it into yet another disposable plastic property, to sell burger king cups for a few weekends and then vanish forever. This was a golden opportunity to turn this into something organic and beautiful, to return the property to the people who grew up on it, who spent their whole lives imagining that world and the things that could be in it. The universe could really have grown, evolved, reflected the times while harkening to the past. But no. Instead we get Abrams, the guy who turned STAR TREK into one long, expensive, convoluted postmodern joke about the original thing we all sort of liked. Yeah, it made a pile of money. But no one felt love for it. It inspired no one to dream, to imagine, to make their own costumes and fan movies and slash fiction. They just paid for it, watched it, and forgot about it. Fuck.

Fuck man. It just really sucks.

(Still, I like Von Sydow, and it’s nice to get a couple interesting actors in there, Isaac, John Boyega, etc. I always forget Von Sydow is still alive and so it makes me unduly happy to see him pop up in something else. I even watched BRANDED because he was in it, true story. Maybe if this whole STAR WARS thing doesn’t work out he and Dario Argento can make SLEEPLESS 2, so at least that’ll be a net gain for the world.)

Part I: The Last remnants of the Old Republic have been swept away.

So by the time December 18, 2015 rolled around, I was not a happy man. Nor, honestly, was I particularly sad man. I was a resigned man, someone who finally understood the way the cultural snake inevitably eats its own tail. I was philosophical. And probably more than anything else, I was annoyed that we were even talking about this stupid thing every minute of every day, and eager to put the whole thing behind me. So I just gave up and went and watched it.

And it was, you know, OK. Some good stuff, some workaday stuff, some pretty bad stuff. Mostly in that order.

The big problem with STAR WARS VII: THE FORCE AWAKENS is that it’s essentially three movies. Which is to say, it has a very rigid three-act structure where each act is so remarkably distinct from the others that it almost feels like an anthology. Perspective, characters and conflict shift so abruptly that, ironically, its achilles heel ends up being exactly the same as the prequels: a crippling lack of clear character arcs or even a consistent perspective on what the essential conflict is.

If I had to guess on who is to blame for this, I actually might spare my old nemesis J.J. Abrams of some of the shame here. Obviously he signed off on it, and it’s his name in the final credits, so he bears some of the responsibility, and brings plenty of his own irritating tendencies to the table. But the final product here has the unmistakable fingerprints of too many corporate masters, requiring too many script re-writes (the final script is credited to three writers; I’m guessing there were more) each pulling what might have once been a solid premise in ten new directions. Eventually, threads start to snap and the whole enterprise deflates and flutters away. Like JURASSIC WORLD a few months prior, this script is an ungainly mish-mash of several different movies, some better than others, but all clearly the product of radically different lines of thinking about what the plot of this movie should actually be. Individually, any one of them might have worked, but together, they turn into a self-defeating jumble which starts out with some genuine energy but gradually sags under the weight of cumulative weight of too many false starts.

For a while, though, things go pretty well. The opening gets right to the intriguing premise -- Luke Skywalker has disappeared, an organizing mystery which the will motivate almost exactly ⅔ of the movie before it is forgotten completely -- and quickly serves up both Max Von Sydow and Oscar Isaac, which is obviously something every movie should aspire to. Of course, you may note that in my final rant prior to seeing the movie, I did say that my biggest excitement here was to see Von Sydow in the STAR WARS universe. Well, it was fun while it lasted. Maybe he has a twin or something. Or they later give him a replacement robotic head. Losing a major appendage to a lightsaber has always been more of an inconvenience than sticking point in the STAR WARS universe.

The movie takes its time introducing us to our main characters. Both Isaac and Von Sydow seem important at first, but they’ll turn out to be minor characters, at least in this episode. Instead, the film sets its sights on resourceful desert-planet scavenger and mysterious-backstory-sporting tough girl Rey (no last name, like Prince) and reluctant stormtrooper Finn (also no last name), who are thrust together through a chance encounter with the McGuffin (a map which reveals Luke’s location) and find themselves on a quest to deliver it to the right hands, at the prompting of a wise old mentor. Sounds, uh, kind of familiar. But this part, at least, works.

Here’s the good news: Both Daisy Ridley (as Rey) and John Boyega (and Finn) are absolutely delightful. The three co-writers (one of them, Kasdan, a veteran of arguably the best STAR WARS film, though also DREAMCATCHER) know their way around banter, and the two actors sell it with a commitment to the two guiding principles of STAR WARS acting --say it faster and more intense-- without succumbing to the woodenness which plagued the prequels. And that’s not nothing. I mean, as much as I enjoy and defend the prequels for their boldness and imagination, the first 40 minutes or so of THE FORCE AWAKENS feels more distinctly human and alive than any STAR WARS film since, if we’re being perfectly honest, probably THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK (I love JEDI as much as anyone, but it’s not a film which is especially interested in the rapport between its human characters). Rey and Finn are unique characters, clearly a part of the STAR WARS universe but also rather unlike anyone else we’ve ever met there. They have their own rhythms and motivations and their chemistry together --their excitement and terror at the prospect of an adventure, their heady, surprisingly earnest joy in their unexpected companionship-- is surprisingly potent. Though the over-complicated deus ex machina which facilitates their meeting adds needless fat to what should be a relatively straightforward Campbellian plot --girl meets boy, they find a mystical artifact, and go on a journey to return it to its rightful owners-- I cannot tell a lie, there’s a genuinely adventurous, intoxicating sense of cheerful fun to be had here.

But herein lies the problem. I think I would genuinely like to see Rey and Finn go on an adventure. And perhaps in the original draft -- if we’re to believe original screenwriter Michael Arndt-- the story did focus on this tale, placing the obvious protagonists of this story at the forefront and giving them the adventure tale that the first third of the movie perfectly sets up. But remember, Disney paid 4 billion dollars for this property. Billion. With a “B.” And I have a terrible sense that with that much money on the line, someone started to fret a little that this was starting to sound worryingly different from the other movies in the series. Abrams, remember, was hired onto STAR TREK to take the same familiar characters from the beloved original and re-introduce them to a new audience. Nothing scary or new required, just a reshuffling of familiar trademarked properties to skew younger. That’s the kind of safe return-on-investment intellectual property stewardship that corporate likes to see. That they’d be betting on audiences to embrace a new set of characters, who had not been extensively focus-tested and thoroughly market-vetted with instant name-recognition among the lucrative 18-34-year old viewer demographic… well, that may not have even occurred to them. So when they started to flip through page after page of script without a single familiar brand name… that worry started to bloom into outright panic. 4 billion dollars. Billion. They didn’t pay that much to throw in their lot with someone named “Rey.”

And so, when the credits roll, Ridley and Boyega are credited a distant 5th and 6th (for comparison: that’s the same billing Ian McDiarmid and Anakin’s Mom got in PHANTOM MENACE). Because the minute their adventure actually begins in earnest, the script re-introduces Han Solo, and from that moment onward it gradually forgets about the kids and becomes ever-increasingly slavishly devoted to recycling the familiar elements of the previous movies (by which I mean, almost exclusively the original trilogy). Ridley and Boyega never disappear entirely, but starting from the moment that Harrison Ford appears on-screen and almost imperceptibly escalating every minute thereafter, their presence in the movie becomes increasingly perfunctory. Finn gets his obligatory Campbellian “hero rejects the call” moment, but then is back on board immediately and without any fanfare. Rey gets a surprise call to fate, but any explanation or impact from it is fobbed off onto the next unlucky sonofabitch to be asked to re-attach the loose ends leftover from this installment. Meanwhile, Han gradually takes over as the de facto protagonist, and a steady stream of familiar faces and recycled plot beats rise to gently meet him. It is Han who has the climactic moment, and the only real dramatic arc which ever materializes in the whole movie.

This is a disappointment, and an unambiguous step back from the movie’s best instincts, but it’s not a complete disaster. Ford, for his part, is absolutely the most awake I’ve seen him in a long time, re-discovering his scoundrel’s charm in a way which I honestly did not think he was capable of anymore. His brief moments with Leia (Fisher doesn’t really have anything to do here except look concerned, but she’s fine) legitimately recapture something of their prickly chemistry. And even more surprising, in his final climactic scene, he even finds something kinda new in the character which feels natural and earned. It’s a little obvious and not especially ambitious, but nonetheless it feels like an honest attempt at evolving, not just recycling.

But… while the surface details here may work OK, the fundamentals do not. Because regardless of how good Ford is, this just plain should never have been his story. The reason he’s along for the ride, in a Campbellian sense, is in the role of wise old mentor. And he makes a good mentor for both Rey and Finn; he embodies their rebellious, self-reliant streak, their reluctance towards heroism, and, ultimately, their shared heart of gold. But wise old mentor characters are not supposed to have their own arcs. It’s the hero’s journey, not the wise old mentor’s journey. You remember Alec Guinness having a subplot about reconnecting with his estranged son in A NEW HOPE? Did you think THE LOVE GURU made for good watching? Mentors, mythologically speaking, are important as guides, and are by definition not the one with the conflict. And in a fantasy tale like this, it’s a zero sum game: every minute we spend building Han’s arc to a resolution is a minute we’re neglecting momentum on the actual heroes here, who are ostensibly the kids (not that you’d know that from the structure of the final act, which posits them as tertiary sidekicks until they finally emerge for a final duel, primarily through a process of attrition.)

Pre-Abrams screenwriter Michael Arndt has talked in interviews about struggling with introducing Luke Skywalker into the script, explaining that “every time Luke came in and entered the movie, he just took it over. Suddenly you didn't care about your main character anymore." That’s a real problem. But, guess what, substituting Han for Luke is no better. This is one of the most iconic characters in all pop culture, played by one of the most charismatic movie stars of all time, and the movie is understandably every bit as star-struck as the characters, leaving Abrams and Kasdan (and, ahem, Disney) either unwilling or unable to resist bringing Han to the foreground and leaving everyone else in his wake.

Could this ever have worked? Possibly. CREED is a sterling example of re-introducing our former protagonist in the role of the wise mentor. And it hardly short-changes Stallone, giving him a big, meaty role with his own subplot and conflict to overcome -- but the structure of that movie is stubbornly insistent that the title character is the true protagonist. Stallone’s (spoilers for CREED) cancer subplot and his alienation of Donny are resolved right at the start of the final act, and the climax is a challenge for Donny alone to overcome, with Rocky looking on and supporting, but, crucially, not directly involved. FORCE AWAKENS, structurally, doesn’t do that. It has a climax with several parallel threads (no doubt clumsily aspiring to the splintered narrative finale of RETURN OF THE JEDI) but unwisely locates Han’s character arc as the emotional touchstone here. The final duel between our two ostensible heroes and the arguable villain is chronologically the end, but is curiously unbound from any of the characters’ actual defining emotional arcs, if the vestigial hints of things to come which are hinted at in the first 45 minutes can even be called by that name. What, exactly, this confrontation means to the participants is a matter of such thorough disinterest from the script that it might be better described as willful ignorance. These three characters have interacted only briefly, and have little personally invested in their conflict. There’s no narrative or psychological need for this confrontation; they just show up and fight because, you know, STAR WARS movies are supposed to end with lightsaber fights, and someone’s gotta do it.

Thus, we are stuck with a movie that, however you slice it, posits itself as the pilot episode of a TV series more than an independent artistic work. It introduces some characters, vaguely hints at some of the conflicts they may develop at some point in the future, teases us with some intentionally obscure mysteries, throws in an action sequence, and then calls it a day, content that its job is done. Infinitely more than any STAR WARS film which has preceded it, this is a movie which by its very nature feels incomplete, all setups with no payoffs. Simply put, it’s not a story. It’s the setup for a story. I suppose in our increasingly serialized and franchise-frenzied world, this may not be a problem for some. But for someone who actually cares about film as an art form, this approach seems lazy in the extreme, unsatisfying at best and shamelessly craven at worst. It is not the work of someone with an exciting tale to tell; it’s the work of someone who needs to deliver a platform to launch a product line by a particular date, and assumes that eventually down the line someone else will work out the details of the story part. And it’s not out of the question that someone will: while I don’t have any hope that the lamentable Colin Trevorrow of JURASSIC WORLD will have anything remotely watchable to contribute with his promised EPISODE IX, Rian Johnson (LOOPER, BRICK) does have at least a shot at taking the foundation laid out by Abrams here and building something interesting and worthwhile out of it. If he does, this will all look a lot better in hindsight. But even so, I doubt it will be a movie which anyone has any particular desire to return to years from now. And that is due almost entirely to the final act, when it abruptly hurdles itself off-course in as shockingly poorly conceived a narrative turn as I dare say I have ever seen in a film.

That sounds more hyperbolic than I probably mean for it to. There’s nothing outright incompetent about the back end of FORCE AWAKENS; nothing anywhere remotely close to some of the stunningly amateurish low moments of the prequels. While it descends into withering mediocrity with an enthusiasm bordering on mania, it maintains the standard grimly mechanical competence which defines all of Abrams’ work. It’s simply that from a storytelling perspective, the final act of the film is so suicidally divorced from anything that came before it that it might qualify as the one genuinely ballsy thing about this film, were it not so utterly bereft of any reason to exist on its own.

Let me put it to you this way. The first words that appear on screen here are “Luke Skywalker has vanished.” The first scene finds a mysterious figure giving information which will lead to Luke Skywalker. Both the villains and the heroes desperately want this information, and for unclear reasons both sides seem to think the most important thing they can do is find Luke Skywalker. Our two heroes are brought together when they find a droid that holds the map to Luke Skywalker.* They connect with a wise mentor (and friend of Luke Skywalker) who guides them about where to bring this vital information about Luke Skywalker’s whereabouts.** One of them improbably finds Luke Skywalker’s old lightsaber and sees him in a vision. And finally, one of our heros is captured, because the villains want her to reveal the secret hiding place of Luke Skywalker. So then, for the climax, they have to blow up a Death Star. I mean, obviously.

As I hope that plot summary demonstrates, this isn’t just shoddy storytelling, this is a bizarre, almost surreal turn of events. The whole movie, from the first sentence onwards, is about one specific journey. And then, wham, out of the blue, right at the start of the third act, the villainous teenage general just says, ‘Well, it looks like we’re not going to find Luke. Let’s use our superweapon instead.’ What superweapon, you ask? Why, the one which for some reason no one ever mentioned before. It’s like a Death Star, in that it’s a planet-sized space station which destroys planets. But get this -- IT’S WAY BIGGER! They even put a picture of it up next to the old Death Star, so you can see, yup, definitely bigger. Total game changer. Anyway, it didn’t seem like a big problem for the first ⅔ of the movie until the screenwriters gave up trying to figure out how they were going to resolve the “Where’s Luke?” story. But since the rebels still don’t seem to have realized that if a giant superweapon is going to destroy the planet they’re on they can just, you know, leave in their spaceships, destroying Death Star Part III suddenly becomes the sole interest of the script and all the characters thereafter.

Of course, it doesn’t help that we’ve already done this twice, and it also doesn’t help that even though this new ultra-weapon is supposedly so much bigger and scarier, it turns out to be surprisingly easy for a 73-year-old, a former janitor, and a wookie, to walk in and blow it up (there seem to be about five people and no locked doors in this supposed massive base. This is what happens when you put a bunch of sullen teenagers in charge of your superweapon). Shit, this is the third massive super-weapon that Han Solo can paint on his fuselage, it’s probably getting to be a bit of a chore by this point. He can do this shit in his sleep. But whatever, I could deal with derivative. The problem here is that this entire incident --which makes up the entire fucking climax-- doesn’t have anything to do with anything else that came before it. Not a single established fact about any of the characters or the plot up til this point plays into this whole “Another Death Star” thing in any meaningful way. It’s poorly established how it came to be, how it works, where it is, what it’s purpose is, or what the stakes are, because it all has to be rushed into a few exposition scenes before we’re off to destroy it. As such, it just feels completely trivial, in addition to being laughably recycled and hilariously unchallenging for our heroes. Nobody really has anything invested in doing this, they just have to do it because, you know, STAR WARS movies are supposed to end with Death Stars blowing up.

Nothing about this series of events arises naturally from the stories or characters, even when it obviously could -- for Finn, at least, this is a return home, and he’s about to be complicit in blowing up all his old co-workers. I mean, our introduction to the character is his horrified reaction at watching one of his fellow troopers die in front of him. Surely this is affecting him in some way? Well, as far as the script is concerned, the only thing that interests him here is getting some snarky revenge against his shitty ex-boss.

Rey --as close to a main character as the film is able to posit via the medium of total time on-screen-- is given exactly one (1) hint of motivation during the film’s duration, which is that she wants to return to her desert home planet to wait for the return of her mysterious family. Is her stopover on the Death Star causing her anxiety that she might miss whoever she’s waiting for? Does something which happens here cause her to abandon this deep need, which seems to be at the very bedrock of her character? The script doesn’t even offer an empty gesture towards any of this, it’s not even on the radar. There’s no conflict here for the characters, and hence none for the movie.

This all adds up to a last act which is criminally undernourished. Like Abrams’ other films, it deftly assembles the ingredients of the sources it’s trying to emulate --a dramatic confrontation between father and son over a gaping chasm, x-wings flying into the weak point of a planet-sized superweapon, a climactic lightsaber duel between good and evil, even Carrie Fisher standing over a computer screen, looking concerned while doing absolutely nothing valuable-- but throws them together haphazardly and without regard to why they fundamentally worked in their original context. And so they don’t work. It’s a shopping list, not a meal. They don’t even really have the dignity of failing, since the film doesn’t even seem to be trying to do anything other than superficially resemble an old movie that we liked. The entire final act is an aside, pure and simple; just a meaningless incident stuck in here to kills some time between the obvious beginnings which are being set up in the opening acts, and the continuation which will have to happen next time around. It’s more reference than plot point, more simulacrum than story. None of the characters --save, of course, Han-- make any meaningful progress in their own arcs,*** they’re simply told they have to blow up something they’ve never heard of before, and 40 minutes later they’ve done it and can go home, more or less completely unchanged by their experience.

It is this strange divorce from meaning that turns an already shallow and uninspired retread into something rather actively enervating. Narrative energy just leaks from the screen as this tiresome plotline goes on and on. That’s bad enough in itself, but to make matters worse, it completely sucks the energy out of the tacked-on epilogue when the movie briefly remembers it’s actually supposed to be about Luke Skywalker right before the final bell sounds. There’s 90 minutes of buildup as to where Luke is, and then 45 minutes of completely unrelated, random bullshit, and then in the last 5 minutes they clumsily slump to a depressing non-resolution of a cliffhanger.

We knew this going to happen eventually, so it’s probably even worse to fob it off as a lame teaser for the next franchise sequel than it would be to just end things more neatly and start fresh next time with a big long-anticipated meeting that we could actually get some mileage out of. If the filmmakers were really serious about this stupid Death Star III thing and the “shocking” death of a beloved character, they ought to at least have the confidence to end the film with an appropriate denouement for these things. NEW HOPE ended with a huge celebration; SITH ended with a funeral; both JEDI and PHANTOM MENACE ended with a celebration and a funeral. Either or both of those things would have been appropriate here (I know blowing up Death Stars is getting too routine for these guys to throw a huge ceremony every time, but maybe just a tasteful after-party?) and might have at least offered some vestige of emotional closure. Instead --perhaps acknowledging that nobody here really has a lot of investment in what just happened-- it just immediately returns to the “where’s Luke?” plot for its remaining five minutes.

This is a bad move, partly because of the clunky way the storyline gets so easily resolved at the last minute (turns out one character knew all along and just didn’t say anything), but mostly because after all the build up, the final appearance of Luke ought to be a real exciting moment. But by this time, the momentum has been so thoroughly ground to a halt that they resort to a deeply unappealing spinning helicopter shot to try to convince you you’re excited by what should by all rights be the movie’s big money shot. And since it doesn’t actually go anywhere, the reveal is all you get. Oh man, there’s Luke! I forgot all about the quest to find Luke, I wonder what he’s going to have to say about… oh, well. I guess next time.

Part 2: “What’s in there?” “Only what you take with you.”

The flubbed last act leaves a sour taste, but the movie as a whole is eventful and ingratiating enough to get by. Yeah, it’s narratively messy and larded up with over-busy plot threads that unsatisfyingly go nowhere, but that’s pretty par for the course on any big-budget studio movie these days; these things get overwritten into incoherence as too many studio cooks try to add their own pet spice to the broth. This is the nature of the beast, and in the context of the depressingly low expectations we’ve learned to accept with the current studio status quo, FORCE AWAKENS is not a particularly egregious offender. It’s probably no worse than whatever AVENGERS sequel has premiered most recently to whenever you’re reading this (though the Marvel films usually spread out their most unpalatable franchise-servicing flab over the course of a whole two hours, whereas here it’s all displeasing backloaded into one long burst, and hence more grating and noticeable). Compared to dadaist anti-narratives like JURASSIC WORLD or AMAZING SPIDER MAN 2, it’s positively elegant in its straightforward storytelling.

And, of course, you can’t meaningfully criticize this film without adding, “but obviously, it’s better than the Prequels on almost every imaginable level that has to do with acting or storytelling.”

And yet. And yet.

The problems with the prequels are obvious; they’re full of wooden line readings, they’re seemingly randomly plotted in ways which bizarrely skip over important moments, they’re full of opaque, impossible-to-relate-to characters with terrible chemistry, and all that is lightly sprinkled with some truly cringe-y comedy. FORCE AWAKENS avoids nearly all of those things; it has much more likeable, relatable characters, more camaraderie, some legitimate laughs, and --absent the final act-- at least the opening notes of a fairly classically structured hero’s journey, played, at least generally, with a sturdy if unimaginative competence. It feels a little incomplete as a film, but presumably subsequent directors will finish the story and this stopover will be more digestible in its context as the first part of a three-part drama, wherein the dropped threads here find a more satisfying destination. So you can’t really hold that against it. At least, not yet (although you also can’t help but note that A NEW HOPE, despite having an almost identical plot, doesn’t have that problem at all).

On the surface, anyway, this movie is a big step up from the prequels, handily avoiding their most notable failings. But like its most telling failure of imagination, the bigger, Death-Star-ier “Starkiller base,” the movie feels designed to look the same and fulfill the same function as its previous iterations, but turns out to be surprisingly hollow.**** It’s not just the final act which is derivative, it’s the whole thing; there’s hardly a single detail in the film which doesn’t seem backwards-facing and referential. The Abrams version of forging into new territory is hobbled by its relentless obsession with re-skinning known quantities from the old movies and hiding behind superficial changes or crude reversals. Yes, it’s another young orphan with a secret parentage who grew up on a desert planet and finds a droid who holds a map which needs to be delivered to Princess Leia and on the way discovers an innate gift for The Force. But this time, it’s a girl!

This is not me being a nitpicky buzzkill here; this is an intentional choice on the part of the filmmakers, and one which they openly played up. And, of course, it’s hardly limited to the protagonist and the final act; rife throughout the entire film are obvious surrogates, reflections, references, and flat-out retreads. I would not be at all surprised to learn that not only are the story details similar, but that the film is deliberately edited to mimic the rhythm of NEW HOPE (even the timing of shots seems familiar in several sequences). And this was the plan all along. They set out with the specific goal of making something “familiar,” as Abrams euphemistically described it. The new movie "needed to take a couple of steps backwards into very familiar terrain" and use plot elements from previous Star Wars films, he said in early 2016.

That this was done with callow commercial concerns in mind is hardly debatable; that it was a good move anyway seems to be a matter of somewhat greater dispute. I mean, people liked this one, and they hated the prequels. So maybe, whatever his motivations, Abrams was onto something. Maybe the problem is that Lucas got away from his roots, flew too close to the sun, forgot the lessons he learned from ol’ Joe Campbell about mythology and simple, elegant storytelling. Maybe Abrams was was right to return to the fount, to rely on what we know works, what we know people want. The first spoken line of dialogue is “This will begin to make things right,” which is obviously what a lot of people hoped Abrams would accomplish, turning things around from the much-hated prequels and getting back to the roots of the series. That the film is a concerted effort to do just that is obvious in every frame. “Chewie, we’re home!” Han Solo exclaims, in his first spoken lines. In context it makes sense, but it’s obviously a line which carries a lot more meaning than just a return to the Millennium Falcon. This is a movie which sets its entire mission on assuring us that, yes, you can go home again. And at times it works. There are moments where you can’t help but admit, yeah, this does feel like the STAR WARS of your nostalgic memory.

And yet. And yet.

For everything that works, I just can’t shake the feeling that this approach is always going to be chasing the dragon. At its best, it’s an adequate reminder of what the real thing feels like, but somehow, despite its fastidiously cultivated gallery of the comfortingly familiar, it never feels like the real thing itself. It’s too safe, it’s too much the same to generate the kind of immersive awe which Lucas’s movies, at their best, were able to conjure. And it is powerfully galling for an enterprise with so many advantages to be simultaneously so unashamedly unambitious. I mean, this movie was guaranteed to make money. There has never been a more sure thing in the history of Hollywood, and that includes the movie THE SURE THING. STAR WARS is almost certainly the most recognizable franchise in the world. It had the entire financial and commercial support of a multi-billion dollar company, which promoted it so relentlessly it managed to venture into areas of corporate synergy even Lucas would have turned down. And even if they hadn’t spent a penny on advertising (and the spent many, many pennies) the media was hanging on every little detail of the production as if this was a missing pretty blond girl. A rich missing pretty blond girl.

So if ever there was an opportunity where it was safe to really swing for the fences, this had to be it. And instead, Abrams and company decided to bunt. It gets them to first base, and leaves the rest to the next hitter. (That’s a sports metaphor, I believe.) Maybe that wouldn’t be such a problem for some scrappy, low-budget indie effort, but for a movie with so many advantages, it can’t help but be a little disappointing. It’s not that this is a terrible movie in itself, it’s just that you can’t help but be a little depressed at the idea that the greatest ambition of this 300 million dollar can’t-miss sequel... is to emulate, as closely as possible, an 11 million dollar movie from 1977.***** And you might well say, “sure, Mr. Subtlety, welcome to the concept of big-budget studio movies.” I mean, “Surprise! Studios are run by artistically bankrupt hacks who want a safe, predictable product which easily parlays into lucrative licensing opportunities, and have no incentive whatsoever to try anything different and potentially risky! Welcome to planet Earth, I see you’ve arrived recently.”

And of course, you’re right. But you know what, STAR WARS used to be something different. Whatever Lucas’s problems are --and they are many-- being a callow, cowardly corporate drone was never one of them. For all the merchandising that he infamously indulged in, his motivations were obviously much more esoteric, to the point of actively ignoring what might have made good financial sense. After FORCE AWAKENS was released, he bemoaned the new, market-driven approach to his classic series in a now-infamous interview on Charlie Rose: "They wanted to do a retro movie. I don't like that. Every movie, I worked very hard to make them different ... I made them completely different—different planets, different spaceships to make it new." And it’s hard to argue that he didn’t succeed in that goal. Not only does every film introduce a whole universe of new aesthetics and images, they’re all also motivated by a relentless, restless desire for technical innovation. From NEW HOPE onward, Lucas’s rallying cry was always that he wanted to do something that had never been done before, see things he’d never seen before. Sure, we’d all be happier if we’d never been introduced to Jar Jar Binks, but the character’s groundbreaking technical innovation cannot be disputed, and he --and the rest of the film-- unquestionably ushered in the modern age of digital special effects, almost singlehandedly. Both the Original Trilogy and the Prequel Trilogy fundamentally changed the way movies were made, even changed the way we thought about movies. You ever hear the word “prequel” before THE PHANTOM MENACE? Now they’re practically as common as sequels. We can argue all day about the inherent quality of the things Lucas introduced --though for all those who feel the prequels ruined cinema, I’d like to remind you that there are plenty of people who argue the original trilogy ruined cinema even more, ending the American New Wave and ushering in an era of exactly the kind of big studio tentpole summer movie which we currently hold in such low regard. But good or bad, Lucas spent a career pushing forward, searching for the new.

FORCE AWAKENS is nearly relentless in its commitment to not being new. It openly wishes only to give the people exactly what they already know they like. Sometimes it does this rather elegantly, as with its patient introduction of the characters. Other times, it does it rather clumsily, as with its listless, recycled climax. Lucas, in the same Charlie Rose interview, described the process of making the new film: “They looked at the stories and said, ‘We want to make something for the fans.’” And frankly, I doubt Abrams and co. would fundamentally disagree with that assessment; they might even consider it a compliment. But it’s telling that Lucas describes his process rather differently: “All I wanted to do was tell a story of what happened. It started here, and it went there.” I’m not necessarily convinced that’s exactly true --presumably someone with a driving need to tell a story would work a little harder at it than Lucas’s work on the prequels indicated he did-- but as a criticism of THE FORCE AWAKENS, it’s hard to ignore. This does not ever, even in its best moments, feel like a story which would need to be told if there wasn’t a financial incentive to think up more STAR WARS sequels. STAR WARS started out as an idea --and a weird idea, one that almost no one believed in-- and found its audience. Now, they’ve found their audience, and they’re searching for ideas. Those are two fundamentally different ways of entering the creative process, and they affect the end result in ways which are subtle but surprisingly deep.

Lucas made his six movies for his own complicated, esoteric, maybe even megalomaniacal reasons, but there’s no mistaking the man behind them. His weird sensibilities are everywhere. He named his villains in PHANTOM MENACE after prominent Republicans he didn’t like. He modeled Chewbacca after his own dog (who also lent his name to Lucas’s other classic trilogy, INDIANA JONES). Hell, Mark Hamill successfully got the part of Luke Skywalker by modeling his acting on Lucas’s behavior, correctly realizing that Lucas saw himself as the hero. Are these marks of profound artistic genius? Perhaps not, but they are marks of vision -- of intention. There’s no comparable intention to be found in THE FORCE AWAKENS. I do not think for a second that Abrams or anyone else would have felt compelled to tell this story, had they not been given an assignment to think up some stuff and put a STAR WARS logo in front of it. It’s not personal. It’s just business. And, I think, it’s rather more empty for it.

And of course, the story is only part of it. And probably, truth be told, not even the biggest or most important part of it. Lucas claims he made the films because he wanted to tell a story, and I think on some level that’s probably true -- you don’t imagine yourself as a space-fantasy warrior-monk on a hero’s journey without having something invested in the tale-- but I think it’s equally obvious there’s more to it than that, and it’s why I used that word “megalomaniacal” in the previous paragraph. I’ve often heard Lucas bemoaned as “lazy” for his half-assed characterizations and shaggy storytelling in the prequels. But remember: he didn’t have to write and direct them himself. If he wanted to just be lazy, he could have hired safe, predictable studio guns (you know, J.J. Abrams types) to crank out sequels and spinoffs on time and under budget until the franchise was run into the ground, like Disney is obviously planning to. But Lucas decided to do it himself. Now, there are definitely aspects of the prequels which are objectively bad, and even things which Lucas freely admits he didn’t really care about. I mean, he openly says that he pretty much improvised the plot as he went along. But not caring is not the same thing as being lazy. Alfred Hitchcock openly admitted he didn’t really care at all about the process of filming and working with actors -- was he lazy? No, he was just interested in other aspects of the process. Hitchcock’s love was for the process of planning and storyboarding, crafting a blueprint of the telling of a tale in minute detail. In Lucas’s case, he’s manifestly much more interested in the tech and the worldbuilding of the series, and he put enormous personal effort and resources into it.

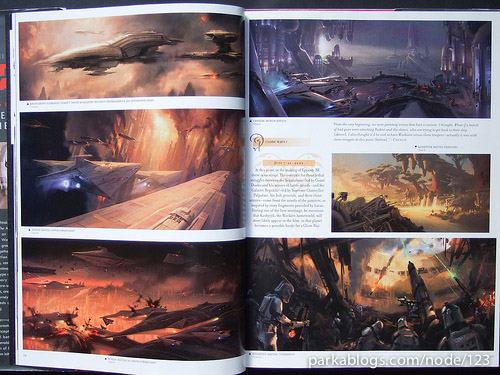

If you’ve never read them before, take a peek at the Art of Star Wars series published by Del Ray, which give the visual design history behind the iconic images in the STAR WARS trilogy. Essentially anthologies of production art, the books about the Original Trilogy were published years after the fact, but their prequel counterparts were put together during and immediately after the production, and feature a chronological structure which brilliantly illustrates the evolution of concepts from free-floating whimsy in George Lucas’s brain all the way to the big screen. The art is stunning, of course, but the most illuminating thing about these books is the insight they subtly give into Lucas’s creative process. Long before the script was done, hell, before the basic story was done, Lucas was intimately involved with the design meetings, throwing out ideas, examining generation after generation of concepts, slowly guiding the process and being guided by it. His signature and commentary are on every single piece of concept art in the book, from things he immediately nixed to ideas he slowly and meticulously chaperone from their rough early shape into their final form. And by the way, what was he supposed to be doing during this time? Writing the script! But the script was in a fetal stage as the concept artists furiously crafted the universe the script would, supposedly, depict -- and, unbelievably, as the book moves on you can see how the images themselves end up shaping the script. Character designs that speak to Lucas get written into the finished text. Images he OK’s for further exploration gradually dovetail into the story.

This demonstrates something which, in retrospect, should have been immediately obvious: Lucas may have begun his career as a storyteller, but his great talent --and his almost single-minded fixation-- is in worldbuilding. And that is what he has devoted his time, energy, imagination, and resources to. Towards the end of the prequel cycle, a cinematic mentor of mine -- in fact, the very person who had originally inspired me to reconsider the value of those prequels-- was frustrated enough with the poor storytelling that he bemoaned Lucas as “A sad old man obsessed with playing with his toys.” Frankly, I don’t know that he was exactly wrong, but on the other hand, I think it is this very fixation which made STAR WARS what it is. We have a lot of hero’s journey tales in cinema, many, if we must be completely honest, far better acted and scripted than even the beloved Original Trilogy. If STAR WARS really is different, if it’s unique, if there is a legitimate reason it has endured this long and become, I would hazard to guess, the most pervasive and influential pop culture phenomenon of modern cinema... Well, it could only be its unrivaled ambition and scope as a worldbuilding project. Quite frankly, there is nothing else which even comes close to it in terms of talent, resources and scale. That, I would suggest, is Lucas’s real genius, and his real legacy, and, perversely, the source of his long battle with his own fans. He created a universe so irresistibly rich that it was impossible not to imagine our own stories within it. But for 35 years, Lucas ruled that universe himself. It was his vision -- but it was also his burden. And even now, he can’t quite give it up. He compared his separation from the series to “a divorce.”

When I first heard that the Lucasverse was under new management, I couldn’t help but imagine --just as everyone did, I suspect-- my own particular imagined STAR WARS tale. I think nearly everyone who grew up on the STAR WARS films has such a story, carefully honed throughout a misspent childhood, perhaps enacted by action figures, perhaps ensconced in prose, perhaps lovingly crafted on home video (maybe even the same home video Abrams himself remembered fondly in his Spielbergian riff SUPER-8) with childhood friends wearing tin-foil costumes and whaling away at each other with toy lightsabers. The fun of STAR WARS is about discovery, about exploring this wild universe, about daring to imagine, just like Lucas did, new and unexpected corners. Directing a STAR WARS movie is the job every nerd has been preparing for their whole life. I honestly found it inconceivable that Disney could even find a director who wouldn’t take this ball and run it headlong into the unknown.

And that, ultimately, is the real bitter disappointment of THE FORCE AWAKENS: given an entire vast, limitless universe to imagine, a universe which, under Lucas’s careful guidance, spilled off the screen in every imaginable direction… Abrams decided to go backwards, to retreat to the familiar. In fact, it’s actually at its worst when it attempts its own worldbuilding (which it does largely out of inescapable necessity, and as rarely as possible). If there is an explanation as to what the dynamic is between the presumably 30-year-old “Republic” government, the “Resistance” which is apparently not affiliated with the government it helped form, and the tacky Space Nazi “New Order,” it’s not to be found in the movie, and I guess it doesn’t matter because one of the three is dispatched offhandedly with no previous introduction. The movie resists any worldbuilding that isn’t absolutely unavoidable, and, tellingly, the few perfunctory gestures it offers in this direction are transparent maneuvers to re-set the scene exactly the way it was in the old movies. Not only do they resist imagining anything new, they actively undo the changes brought on by the end of JEDI. It is intentionally and deliberately calculated to bring us right back to where we’ve already been. It’s more of the same, which is the one thing STAR WARS never was.

Epilogue: A New Hope

Even so, there are reasons for hope. There are seeds planted here which, at least, have the potential to grow into something more ambitious than the soil they’re sown in here. As derivative as the movie is in its in its broad strokes, there are a few elements here which resist easy identification. While Rey is transparently a gender-switched Luke with the addition of an almost frightening terminator-like hyper-competence, Finn is something genuinely new. As a former Imperial grunt turned reluctant hero, he represents one thing we genuinely haven’t seen in the STAR WARS universe before: a real dog’s-eye-view. Lucas’s STAR WARS films were about Heroes and Villains and Chosen Ones and Senators and Princesses. Finn is none of those things -- he’s just a regular guy trying to navigate in a universe which is beset on all sides by larger-than-life movers and shakers with their own agenda. He doesn’t want to be swept up in any of it, but the universe has other ideas. I like that. His story disappointingly peters out in this episode, and he’s practically forgotten about by the end, but moving forward he has the potential to bring something of a new perspective to this story. There’s no character like him anywhere else in the saga so far; hopefully, subsequent directors (who are less reluctant to forge into new territory) will find a better use for him than FORCE AWAKENS does.

And then there’s the one variable I haven’t mentioned yet. By far the most interesting and enigmatic character this time around is the villain, Adam Driver as the teenaged fallen Jedi-in-training Kylo Ren. On the surface, this character is another one of Abrams’s unimaginative reversals: instead of a young Anakin tempted by the Dark Side, here we find a newly Dark Jedi, tempted, apparently, by the light, but driven (for reasons as yet unexplained) to resist his better nature. The script offers no explanation for his situation, nor window into what his ultimate goals and motivations are, but nonetheless his frustration, conflict, and insecurity add up to an unexpectedly complex villain. His backstory is revealed in a bafflingly awkward fashion (mostly clumsy expository dialogue haphazardly crammed into unrelated scenes) but there’s no way around it: Kylo Ren has the makings of an interesting character, and a window into the Dark Side of The Force much more nuanced than anything in the Original Trilogy would suggest (of course, I also think Anakin’s unexpectedly sympathetic descent into evil is interesting, so what do I know?).

And of course, Abrams being Abrams, he all but buries the script with his beloved “mystery boxes,” which is a cheap and hacky trick, but of course you also can’t help but be a little curious about what’s inside. Who is Supreme Leader Snoke (and why is his CG so dodgy in a 300 million dollar movie)? Who are Rey’s parents, and why are they Luke? What, exactly, is a Force “Awakening?”****** How exactly did Anakin’s old lightsaber get from the bowels of Cloud City to a cantina dry storage room? How did Kylo Ren end up the way he is? And, most importantly, what’s the deal with Luke, exactly? Why is he hiding, how did he fuck his whole Jedi thing up so bad, and what is he gonna do to fix it?

It’s the first STAR WARS film to put such a heavy emphasis on mysteries which are clearly aimed at long-term arcs, and the first to end, completely unresolved, with a straight-up cliffhanger (or, more accurately, a cliff-stander). Even if all these mysteries pay off big (and Abrams does not exactly have a stellar track record for producing solutions as good as his setups) I think it would probably have been better to just tell an actual story instead of setting up a bunch of stories to be resolved (or not) at some future point, by someone else. But still, this, at least, is new territory for a STAR WARS film, and evidence that there is a future for this series as something other than a respectful museum piece. But if there is a future here, it is one in which we make some forward progress. Time travel is one sci-fi trope which has never had a place in the STAR WARS universe. It doesn’t suit it.

My mother, who saw STAR WARS in a small Indiana town in 1977, remembers the “jump to lightspeed” scene eliciting a spontaneous standing ovation from the crowd. Abrams might be a little young to remember that, but he’s certainly aware of the power that these films had. He made a movie trying to recapture that sense of awe and excitement by reviving the same stuff which got the applause way back when. But this isn’t small-town Indiana in 1977, and I noticed that the thing which got the most applause this time around was the opening logo. Let’s hope that next time, new director Rian Johnson remembers that those audiences weren’t just applauding the things they were seeing; they were applauding a film which showed them things they’d never seen before. Awe is really a reaction you can only capture once; after that, it’s just nostalgia.

Upon landing on the generic forest-biome planet Takodana, the desert-raised Rey is in awe: “I didn't think there was this much green in the whole galaxy!” she gushes (apparently the educational opportunities on Jakku are somewhat limited). By the time she makes it to to the next woodland planet, though, she’s not as excited. Excitement, wonder -- these things are by their very nature fleeting. The things which fire the imagination do so precisely because they’re novel, because they give the mind something to wonder about, to play with, to expand, take apart, put back together in a new way. But the mind is restless -- once it has explored the ends and outs thoroughly enough, it begins to hunger for something new. Imagination is always the domain of the the exotic -- it fades with familiarity. Nostalgia is just the opposite -- it grows stronger with time, with comfort, with repetition. But for my money, the power of wonder, for all its slippery unsustainable frustration, beats nostalgia every time (in art, anyway). Wonder inspires. Nostalgia placates. They’re both powerful urges, but one pushes us into the future; the other tempts us to live in the past. That dichotomy, ironically, is built right into a slight variation between the scripts of NEW HOPE and FORCE AWAKENS: young Luke Skywalker yearned to leave his backwater desert homeworld and explore the galaxy. Rey, conversely, says she only wants to go back. An understandable sentiment, of course. But would you want to watch a movie where she does? THE FORCE AWAKENS is a movie that banks on the idea that Rey would probably be happier returning home and living in the past, sacrificing the future for a dim, fuzzy memory of something she loved a long time ago, something that left her behind. But for me, STAR WARS is not about going back. “You have just taken your first step… into a larger world,” Obi-Wan Kenobi drolly intones, as an earnest young Luke struggles with the concept of The Force. So did we all, Ben. Now let’s stop reminiscing about that first step, and let’s start exploring.

Cue iris wipe.

The End.

* This is some sort of weird space map which hilariously posits that going to a specific planet requires a treasure-map dotted-line approach.

** His plan, incidentally, seems to be to go to a well-populated area and walk around openly showing off that they have the droid all the bad guys are looking for. This doesn’t seem to make much sense or work out very well for anybody, but I guess who am I to tell Han Solo his business?

*** You could argue Rey’s early steps towards her inevitable Jedi-dom happen during her captivity here, but the fact that she’d eventually train with Luke was already all but established thanks to her vision in the Cantina; she learns she has Force powers here, but how that affects her or her journey as a character is completely unexplored.

**** I think. My understanding is that it’s a big hollow shell built around a sun which it drains of energy, but I could be wrong about that because it’s not communicated very clearly. Anyway, you do have to chuckle at the fact that in this case, Solar Energy is a limited resource, as they basically use up stars and move on. Maybe the next one can have a bunch of solar windmills all around it so they can appeal to the upper-crusty space fascists who want to go green.

***** Lest you be inclined to cry out that I didn’t adjust for inflation, it works out to about 43.5 million dollars in 2015 money. That’s about the cost of Melissa McCarthy’s 2013 film THE HEAT, or the Franco/Rogen North-Korea-bashing THE INTERVIEW.

****** Also: What kind of a stupid name for an evil leader is “Snoke,” anyway? Did his parents use the same baby-naming book as the Count and Countess Dooku? Why is the universe entirely peopled by 70-year-olds and teenagers? Will we ever see Captain Phasma actually do something? When will the evildoers learn not to build superweapons with one extremely vulnerable spot?