Well, as I’ve told a lot of juries over the years, “I can’t really explain why I do the things I do.” I don’t know why, but for some reason over the last two week I’ve watched seven films, made between 1948 and 2010, all of which dramatize the story of Burke and Hare, a pair of murderous Irishmen in 1829 Edinburgh, Scotland. None of them are exactly what a sane person would describe as “good,” let’s get that out of the way right off the bat. But I think there’s something interesting in examining how different artists over the decades have interpreted and tried to tease out different meaning, all from a real historical event which happened more than a hundred years prior. So over the next few weeks, we’ll be taking a walk through a rogues gallery of films that tried to exploit, educate, philosophize, and entertain through the telling of the strange tale of Burke and Hare, resurrection men.

First off, let’s get the facts. 1828 was a shitty time to be alive in Edinburgh, Scotland for any number of reasons. But it was absolutely the best place to be if you wanted to study medicine (or, as we now call what they were doing, “a bunch of horseshit about humors and phrenology”), because Edinburgh boasted some of the most prominent doctors and one of the the most prestigious instructional facilities in the world at that point, the University of Edinburgh medical school. What we would now call the Scientific Method was in its infancy, but one area of medicine in particular was actually making some headway in unraveling the mysteries of the human body: the study of anatomy.

It’s kind of easy to understand why this would be an appealing field for eager young 19th-century doctors. There were lots of things we did not understand about the body yet; for example, “germ theory” itself was just barely on the scene, and the “miasma” (“bad air”) theory of 2nd-century Greek doctor Galen still dominated the medical profession, meaning that, basically, most doctors actually had no fucking clue what illnesses actually were or where they came from. And of course, we were still a century away from discovering antibiotics, so even if they had known, there was exactly jack shit they could have done anyway. Pretty frustrating stuff. But the anatomy… that was something else. The body was there. You could see it, you didn’t even need a microscope. You could see what the organs did, you could see if something was wrong or out of the ordinary with them. Doctors were comically powerless against most of the things that could go wrong with said organs, but at least they could see them and generally deduce why people were dying, and that was in itself a big step forward. Hence, students flocked to the anatomy lectures (the first ever public science lectures in England!) in Edinburgh, and in particular the lectures of one Dr. Robert Knox, a former army surgeon renowned for his anatomical knowledge.

But there was a problem. In order to do anatomy lectures, one would eventually need to actually look at, and preferably dissect, a human cadaver. But human corpses weren’t something you could just find lying around the city streets of Scotland. Or ok, probably you could, but not often enough, and even when you found one, you gotta figure the family or whatever would object to having it spirited away for medical dissection in front of a leering crowd of drunken, whoring 20-something med school frat boys with impenetrable accents. Legally, the only way to get fresh bodies was through the criminal justice system, but since the police were just as shite at their jobs as the medical establishment was back then, they weren’t hanging miscreants fast enough to fill the needs of the burgeoning lecture industry. There had been some talk about changing the law to allow doctors easier access to cadavers, but then some people argued that if we legalized that, what’s next, marriage between a man and a horse!?!??? So that shut things down for awhile on the political side, and, meanwhile, the medical industry was left without a legal, reliable source for anatomical subjects.

Well, say what you will about Capitalism, but man, this is exactly the sort of problem it was invented to solve. And so, a new profession was borne: a clandestine underground market for corpses --the fresher the better-- procured by enterprising graverobbers, or, as they came to be known euphemistically to the point of poetry, “Resurrection men.” A fresh body could fetch a hefty sum, and the doctors in charge weren’t asking questions about the source.

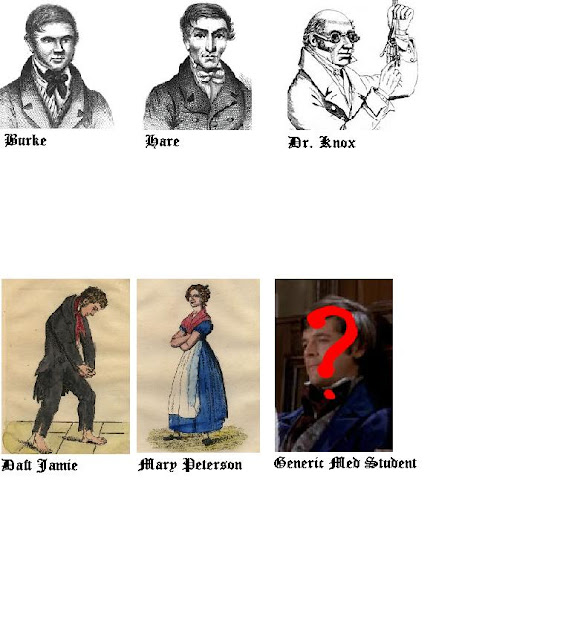

Into this inspiring paragon of free-market utopia stepped two unscrupulous Irish immigrants, both named William. Burke and Hare ended up in the corpse-snatching trade rather by accident, as one would imagine most people did (at the very least, it’s yet another potential path to success that my high school career counselor failed to clue me in on). Hare had married a woman who ran a dilapidated boarding house for vagrants and beggars, and when Burke arrived in 1927, the two began a friendship which would last for a good year and what, by all accounts, amounted to untold barrels of whiskey. Burke found work as a cobbler, and the two appear to have lived rather uneventfully until Nov 27, 1827. That day, an elderly lodger at the boarding house died still owing £4 in back rent, and someone had the brilliant idea of selling the body to recoup the money owed. They initially attempted to sell the body to legendarily dull and unpleasant Professor Alexander Monro III (of whom a young student, one Charles Darwin, wrote, he "made his lectures on human anatomy as dull as he was himself," adding, "I dislike [Monro] and his lectures so much that I cannot speak with decency about them. He is so dirty in person and actions.") but a random student whom the two miscreants entreated for directions mistakenly sent them to Dr. Knox instead. When they were handsomely rewarded with £7.10 ($1,130 in today-dollars), you have to imagine the germ of an idea was quickly born.

Untold pints of whisky and a few months later, the pair couldn’t help but notice that another lodger was on his last leg, and almost certainly worth more to them dead than alive. Only problem was, unlike the last guy, this “Joseph the Miller” character didn’t have the decency to shuffle himself off this mortal coil in a timely fashion, so this time Burke and Hare helped him along, plying him with alcohol and then suffocating him by covering his nose and mouth (a process which resulted in a corpse which showed no outward signs of foul play, and came to be known as “burking” in the vernacular of the time, though why mid-19th-century English was in such dire need for a word to describe this particular behavior is a mystery for which I’d be happier never knowing the answer).

Having broken the murder barrier, the pair was quicker with their next victim, an old woman named Abigail Simpson, who met the same fate as Joseph and fetched a tidy £10 bounty.* In short order a prosperous career as bodysnatching killers was launched, and the enterprising ghouls offed --and sold off-- at least 16 people over the next ten months. They murdered young and old alike, generally relying on guests at Hare’s boarding house (and on at least one occasion branching out to the confused relatives who showed up searching for a missing loved one) and even including a visiting cousin of Mrs. Hare on their list of victims. But of the 16 dead, three managed to catch the popular imagination and become essential to the telling of the story.

The first of these victims was Mary Paterson, a young woman who Burke encountered along with her friend Janet Brown and invited to breakfast. Brown bailed on the breakfast during a spirited argument that erupted between the (presumably intoxicated) Burke and his commonlaw wife, Helen McDougal, which you gotta figure got awkward awfully quickly. When she returned later in the day, Paterson was gone, and would shortly appear on Dr. Knox’s dissection table. Paterson’s prominence in the many fictionalized versions of the story probably arose from the contemporary description of her and Brown as prostitutes (though modern scholars seem divided on this point), and the added savory detail that a student of Knox’s is said to have recognized her during the dissection, having, shall we say, made her acquaintance a few days prior. Obviously, the dramatic possibilities of this last detail were not lost upon various screenwriters over the years.

|

| Mary Paterson |

The second victim to figure prominently in the films is “Daft Jamie” Wilson, often described as a mentally ill young man but from the available evidence more likely what we would now call a savant. An 18-year old fixture of the community, “Daft Jamie” was known for his itinerant, homeless lifestyle, perpetually wandering shoeless through the open-air market known as “the grassmarket” and performing astonishing feats of calculation in exchange for money or food. Jamie was a teetotaler, and hence defied Burke and Hare’s usual MO of “burking” a deeply inebriated victim, resulting in a protracted struggle which involved both killers. Well-known to almost everyone in the area, Jamie was immediately recognized by several of Dr. Knox’s students upon delivery of the body, but Knox insisted they were mistaken and a hasty dissection of the body prior to the lecture rendered it unrecognizable. As far as I’m aware, this one detail is the only official suggestion of Dr. Knox’s complicity in covering up the murder, and curiously I believe only one film version includes it.

|

| "Daft Jamie" |

The final victim in our story is old Mary Docherty, an elderly old drunk lured back to the boarding house when Burke (get this!) convinced her his mother was also a Docherty. That’s some cold blooded shit right there. Unfortunately for our two villains, this was not exactly a masterstroke of criminal cunning, because Hare’s boarding house, where most of the murders occurred, was currently occupied by a family named Gray. Since they couldn’t very well get down to business with a family sitting around (family values and all that), they had to extremely suspiciously eject the boarders in order to do the deed. Also --and I don't know if this is really important, but maybe it's worth mentioning, seems like it might be noteworthy --someone heard an old lady shouting “murder!” during the night, one of those minor, subtle little red flags you only ever notice in retrospect. And also when the Grays returned the next day, the body was still in the house, hidden under a bed which Burke suspiciously would not let anyone approach. And then for some reason the villains actually left the house, leaving the now extremely incredulous lodgers alone in the house with a dead body poorly hidden under a bed they’d spent the whole day suspiciously guarding. In short order the Grays had discovered the body and were off to the police; McDougal encountered them on their way and attempted to buy them off, but they refused and immediately summoned the authorities. For their brave and selfless actions in the face of what must have been brutal poverty to put them in Hare’s house to begin with, the Grays would be forever immortalized on film as heroes who, nah, just yankin’ your chain, they’re minor screen characters at best, and mostly excised from the cinematic tellings of the story. What, you think we want to hear about how some poor family solved a hideous crime at great personal risk and in punishingly dire circumstances? Fuck that. We want blandly handsome medical students and sexy prostitutes or get the fuck out.

|

| Mrs. Docherty (not pictured: the people who actually solved the case) |

Now the authorities had Burke and Hare, as well as their respective better (?) halves, in custody. But they had a problem: there were two suspects with very little evidence directly connecting either of them to the crimes, and it seemed likely that Burke and Hare would blame each other for the murders. If they did, and the state was unable to build a persuasive case against either of them individually, there was a very real possibility that both men might walk free. Faced with this dilemma, the cops cut a deal with Hare (who they apparently believed to be the stupider of the two, and hence less responsible) to testify against Burke in exchange for his freedom. A trial found Burke guilty, but found charges against his wife unproven, leaving three of the four murderous conspirators unpunished. Burke was executed by hanging, and, in an irony which was surely lost on no one, publicly dissected by the very same widely hated Professor Monro to whom he had first hoped to sell cadavers. You know, for science. They also, ah, wrote a sentence with his blood, and tanned and removed his skin to bind a book and craft a handsome calling-card case. For science? Every part of the buffalo, I guess. They also removed his skull for phrenological research, lest you try to derive some slight comfort from the hope that his death actually benefited science in some way.

The Hares and Burke’s wife Helen McDougal, free from legal punishment, were nonetheless quickly threatened by angry mobs and had to be whisked out of the city and, subsequently, out of recorded history. Popular folktales report a mob blinding Hare by throwing him into a lime pit, but no corroborating evidence seems to confirm it. Dr. Knox --never legally implicated in the crimes-- was nonetheless judged complicit by the public, and although he continued lecturing, his career was ruined. Mobs followed him around (apparently people had a lot of free time on their hands back then), surrounded his house and broke his windows, but, ever the stubborn Scotsman, he refused to take a hint and tried to carry on. He eventually moved to London, but he never shook the taint of his association with Burke and Hare. He died in relative obscurity, unable to secure any University position again. Lest you pity him too much, he devoted the final years of his life to crafting evolutionary theories of white supremacy. So, couldn’t have happened to a nicer guy.

The most interesting thing about the tale of Burke and Hare isn’t so much its effect on the course of history, but rather the way it captured the attention and imagination of the public. Folk tales regarding the duo sprang up almost immediately, making it extremely difficult to distinguish fact from fiction in modern times. As early as a year after the murders, satirical artist William Heath was using imagery of the killers to make political points, and a few decades later Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic short story “The Bodysnatcher” borrows obvious story elements. The advent of cinema in the 20th century brought many more adaptations of the tale, as we’re about to discover. The curious thing, though, is that for all the mythologizing and fictionalizing, the tale still seems oddly slippy, resisting easy moralizing and comforting catharsis. And that odd nebulous quality is borne out in the long history of directors adapting the story, trying to figure out what it’s really about and never quite succeeding or agreeing with each other. It is exactly this curious resistance to a simple, straightforward telling that intrigues me, because it means that each iteration has its own subtly different perspective on who exactly this story is even about, much less what it all means. So join me, ladies and gentlemen, as we relive this grim real life story of murder as a philosophical meditation, a black comedy, a horror movie, a sex romp, a Dylan Thomas screenplay, a wacky farce, and a jaunty English folk-rock ballad.

The Burke and Hareathon has begun.

* Some accounts put this murder at the same time, or slightly before, Joseph, but obviously for narrative purposes it works better as a slow escalation, which is what most film treatments include it as, if they include it at all.

1939: The Anatomist (original TV version, based on 1930 play)

1945: The Bodysnatcher (Actually something of a sequel, where Knox, Burke and Hare are mentioned as a precursor, even though the plot also mirrors their story)

1949: The Anatomist (Alistair Sim, Elena Fraser)

1956: The Anatomist (Alistair Slim, Adrienne Corri, TV Play)

1958: Corridors of Blood (Karloff and Christopher Lee star in this horror movie which has strong parallels to the Burke and Hare story, without being a direct adaptation)

1960: The Flesh and the Fiends

1971: Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde (features Burke and Hare as henchmen)

1972: Burke and Hare

1980: The Anatomist by James Bridie (BBC play with Patrick Stewart as Knox)

2010: Burke and Hare

No comments:

Post a Comment