Horns (2014)

Dir. Alejandra Aja

Written by Keith Bunin, based on the novel by Joe Hill

Starring Harry Potter, Max Minghella, Joe Anderson, Juno Temple, James Remar, Heather Graham, David Morse, Kathleen Quinlan

In what may be the single most accurate title of the year, HORNS is about a guy who grows horns. The horns are a major plot point and everything, so it totally makes sense that it’d be a good title. Take that, BANSHEE CHAPTER.

Well folks, here we are, at the very final chapter in the Chainsawnukah adventure which took a goddamn third of a year to wind down. I want to thank you all for sticking with me all these long, lonely months (at least, those of you who did -- readership is down about 70%, so never let it be said I don’t suffer for my art) but here it is, at last, the end. Actually, to be entirely honest I was planning on ending it with RETRIBUTION, but when I caught this movie in theaters two days after Halloween, I knew it was meant to be, this is the perfect one to close off the season, this is the one we’d been circling towards, unaware of the parallel lines of destiny quietly and precisely drawing nearer, those fine threads which pull us inexorably into a future unseen but impending.

This is the story of Ig Parrish (Harry Potter, THE WOMAN IN BLACK), a nice young man who everyone thinks is a murderous sociopath. See, Ig’s longtime girlfriend, Merrin (Juno Temple, 2012 Cursed-to-Live Winner KILLER JOE) was recently raped and murdered. Right after they had a big, public fight. And they found Ig nearby the next day, drunk and babbling about her. So it doesn’t look good. He insists he’s innocent, but even though his best friend and lawyer (Max Minghella, ART SCHOOL CONFIDENTIAL) has so far kept him out of prison, the whole town is certain that he’s a monster, and lets him know in no uncertain terms. And then he grows the horns, so that doesn’t help matters. Boy, when it rains, it pours. And it’s set in the Pacific Northwest, so it’s always raining.

The horns are obviously a cause of some concern for Ig, but, curiously, no one else seems especially rattled by them. Mostly other people don’t even mention them, which I’d chalk up to an excess of politeness except that there are already people spitting on Ig in the street. Instead, the horns seem to have a strange psychological effect on the people he encounters; they notice the horns, but can’t seem to concentrate on them, because they’re too concerned with their own problems. The horns seem to release inhibitions in anyone Ig encounters, turning people into violent street brawlers, arsonists, or sex fiends. Or, they start to spill their most intimate secrets. Which might just prove helpful in finding out just who exactly it was that murdered Ig’s girl.

There’s an obvious tension in that premise, between the extremely grim story about a brutal murder and the possible guilt of our protagonist, the surreal, grotesquely comic havoc he causes as he encounters people he knows (at first to pump them for information, and later, in increasingly nasty ways, to punish them) and the darkly fantastic magical realism of the imagery and iconography Aja employs. Those are tough impulses to balance. Though they’re rarely acknowledged as high art, successful comedy and horror in art are quietly difficult things to get right. Drama, the much-vaunted golden boy of genres, is actually deceptively simple in its mechanics: fundamentally, it’s about accurately communicating a narrative. As long as you can effectively tell the central story, it will succeed. But successful comedy and horror are mercurial things, a delicate alchemy of subtle manipulations of art buried beneath outwardly exaggerated scenarios. Getting either of them seriously right requires a deft touch on the expressive dials of cinema, and a few wrong notes can throw everything off. So getting both of them right at the same time is a rare enough feat that it’s nearly a fool’s errand. Oh, I’ve seen plenty of funny horror movies, but usually only because the horror is softened, its exaggerated nature played for parody instead of terror. It’s a rare film indeed where both horror and comedy can thrive without one or the other being neutered and denatured.

Rare, but not unheard of. Director Alexandre Aja has shown himself to have a striking aptitude for the ephemeral nuances of cinematic tone from the start, succeeding in conjuring the right feel for movies as disparate as the grueling HILLS HAVE EYES remake and the amiably goofy PIRANHA 3D, even when his sometimes shaky grasp of plot mechanics fail him. PIRANHA, for example, is a complete narrative mess that never goes anywhere, and yet it’s impossible to completely write it off because moment-by-moment it so effortlessly captures the sense of straight-faced, cheerful preposterousness which is so much more essential to a movie called PIRANHA than any script could be. The fact that it successfully conjures the right mood, the perfect vibe for the endeavor in spite of its glaring narrative deficiencies is a testament to a carefully crafted cinematic style with a rare emphasis on getting the production details right -- editing, musical cues, particular performance styles, cinematography. PIRANHA falls clearly on the comedy side of the horror/comedy divide (its sequel, PIRANHA 3DD, pushes the genre into disappointing cheap comedy by the film’s end) but with HORNS, Aja proves himself capable of doing something a little more complicated.

|

| There's no Aja-stice in this world. |

HORNS isn’t exactly a comedy, but it’s also not exactly a horror movie, or a mystery, or some sort of weird fantasy allegory. It’s a little of all those things, but never entirely any of them. And that was a problem for a lot of reviewers, who complained that it never settles on a consistent tone or genre. But for me, that’s the whole point; what makes it impressive is its insistence that it’s simultaneously all those things. The various tones fluctuate in intensity, but none ever entirely dissipate, like musical themes deftly woven in and out of an overarching melody. It makes for a wild ride, and a few times Aja almost lets it get away from him (especially towards the somewhat deflated finale) but when it works, it’s absolutely an arresting, unique experience.

Part of that likely has to do with the source material, of course (a novel by Joe Hill [Billy in the framing story for CREEPSHOW**], unread by me). Aja has proven himself an unreliable structuralist over the years (see: the movie-killing twist in HAUTE TENSION, the structureless middle finger to act-based screenwriting that is PIRANHA) and it no doubt helps him to have the story mechanics basically laid out for him in advance. But that seems to free him up to focus on something he’s better at: crafting a strange, dark fantasy world which can unexpectedly erupt into farce or brutality at any given time. Cinematographer Frederick Elmes (frequent David Lynch collaborator, who shot ERASERHEAD, BLUE VELVET, and WILD AT HEART as well as bounty of other gorgeous films, from THE NAMESAKE to HULK (2003) to NIGHT ON EARTH to SYNECDOCHE, NEW YORK) captures the foggy Northwest location with a fairy-tale’s eye to deep mossy greens and warm earth tones, always saturated by the iron-grey sky that looms over everything with a predacious eye. And underneath scramble our characters, your typically attractive and articulate thirtysomething movie actors, but all with an unsettling edge of darkness, looking quietly exhausted, disheveled, scared. People with something to hide.

|

| Lookin' a little horny, buddy. |

Boy, who would have guessed back in 2001 that little Daniel Radcliffe, cast primarily for his startling physical resemblance to a fictional wizard child, would go on to be such a daring and surprising adult actor? He’s tremendously good here, making his tortured character’s oscillations between bafflement, malevolence and despair look effortless and natural, and providing a rock-solid emotional anchor for the whole enterprise, all the while without resorting to showy actorly tics. It’s the very definition of a performance so graceful it looks easy, but potent enough to ground a wild tale with a million possible distractions.

The rest of the cast is rock-solid too. You got Joe Anderson (ACROSS THE UNIVERSE, THE RUINS, bass player Peter Hook in the Joy Division movie CONTROL) as Ig’s jazz-rock-fusion musician brother.* You got Max, son of Anthony, Minghella as Ig’s one loyal supporter and lawyer. You got Kelli Garner (LARS AND THE REAL GIRL, BULLY) as one of Ig’s childhood friends. Heather Graham as a waitress in a quirky Northwestern small town diner (hmmm.. what does that evoke?). And for the parents, you got an embarrassment of riches: James Remar and Kathleen Quinlan as Ig’s folks, and David Morse as the resentful father of the dead girl. And you gotta appreciate Juno Temple in the usually thankless role of the flashback victim. Normally when actresses do this, all they have to do is silently giggle and roll around in bed with our hero in sun-drenched flashbacks to more idyllic times. But a surprising amount of time here is spent on her, and she actually manages to craft something approximating a real character, not just a plot point (the movie has an unusual focus on the past, imbuing the relationships with a surprising amount of complexity and weight across the board). Along with Radcliffe, she manages to add genuine emotional heft to a story which could easily have been a pretty but hollow shell nestled around a generic MacGuffin of a core. Thanks to the strong character work here, that never becomes a problem. Also she gets naked and freaky in a tree, which I believe is one good reason to always hire Frenchmen to make these films.

|

| Planning, people. |

With top production talent behind the camera and a wealth of excellent actors in front, Aja seems confident in his pacing and tone, sometimes indulging in stylish tricks (a spiraling camera to signal the disorientation of waking up drunk, a slippery and nightmarish drug trip taking on both symbolic and emotional abstraction) but mostly seeming content to simply lets the story unfold, as Ig’s new horny powers set him loose on the town. Some of it is goofy fun, but there’s also a layer of real bleakness here; this was really a horrible crime, and everyone’s lives are irrecoverably broken by it. That sense of darkness deepens as Ig increasingly starts plying people for their deepest secrets, and discovering that in most cases, there are things rotting under the surface that reveal the already depressing situation to be even worse than it seemed. And how much of that can you learn before you get tempted to go beyond prying into actual punishing? And how much of that can you do before you turn into a monster yourself? I mean, even beyond the horns thing, which is admittedly pretty monster-y but come on, you think those guys in NIGHTBREED would be impressed by a couple horns? Please.

Which brings us full circle back to our theme from this year: transformation. We talked back at the very beginning --when we were so young and naive and thought this would be well over by December-- about the horror genre as the cinema of transformation. And here is a movie which really hits at the heart of the horror that comes with transformation, both physical and psychological. In fact, that’s really the only sense in which it’s a horror film at all; the most dangerous person here is the protagonist, and he’s had to literally transform himself into a monster in order to do what he has to do here.

|

| Yeah, but you should see the haystack. |

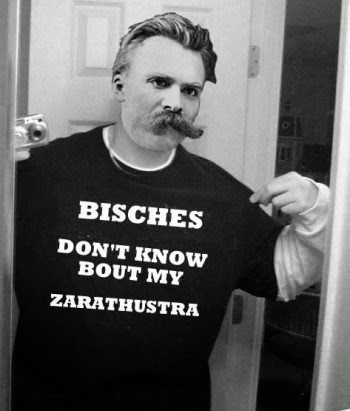

Though HORNS, unlike THE ORDER, has the good taste not to mention it, there’s a lot of that famous Nietzsche quote here. No, not that one. The other one. The one which customarily appears as pre-credit text in movies. “He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And when you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes into you.”

Boy, there’s something to be said about that, isn’t there? For all of our denunciations of the evils of the world and the evil ones who do them, sometimes there’s a lot more of them in us than we’re comfortable admitting, let alone us in them. Those roles of monster and fighter are not as fixed and intragnizent as we like to say, we like to believe, we need to believe. Both dragon and slayer have death as their goal; only their targets differ. At the core, the more the conflict deepens the more the psyches converge -- if you’re capable of hating evil, you’re also capable of becoming the same force of destruction you so oppose, regardless of how you dress it up, the stories you tell to convince yourself it’s different. We can put a pretty face on almost anything, but what lies behind that facade is another story. So of course, here’s a movie about someone who gets a unique chance to crack open the protective outer shell of the people who surround him, and get an unfiltered look at the darkness inside. And there’s a lot of darkness. How many times can you look directly into the abyss of people’s minds before it starts to transform you, too?

The horns themselves are an interesting metaphor, with their obvious connotation to the devilish. ‘People see Ig as a devil, and so that’s what he becomes,’ is the obvious underlying logic of the metaphor. He is transformed by their accusing gaze, physically at first, but maybe also a little bit mentally. (Or, is it the other way around? Does the fact that everyone he encounters --maybe even his family-- believes him to be a mosnter change him first, sow the seeds of bitterness and anger and doubt in him, in ways he only notices when those changes start to manifest themselves physically?) The curious thing, though, is that becoming a literal devil seems to have more effect on the people around him than it does on him. Seeing the externalization of what is either Ig’s actual guilt or his bitterness at how unfair his life has been seems to liberate people to give in to their own worst instincts. If Ig’s horns are the result of his demonization by the town, what are we to make of the way it reflects back on them? And how the secrets they reveal seems to strengthen the cycle?

|

| This is why you always use forehead condoms. |

The angrier Ig becomes as he gets a painful, horrifyingly unfiltered look into the darkest corners of his friends and loved ones’ brains, the stronger his demonic powers become and the more pronounced his physical transformation seems. The movie is intriguing ambivalent about this fact, just as it interestingly withholds judgement about whether Ig may be crossing some kind of line with the punishment he decides to doll out. I can’t help but wonder if this is ultimately an explicitly religious musing on the nature of the devil, of evil. Is the devil --ruler of hell and hence the ultimate arbiter of punitive morality-- really the cause of evil, or is he more of a necessary reaction to it? Can we truly understand how deep evil runs in the world without being corrupted by our desire for violent retribution?

I’m not sure the movie ever quite coalesces into a coherent exploration of these questions, but it mostly doesn’t matter: this one can be ungainly, and it’s constantly threatening to go off the rails (and also coasts through its final resolution more on momentum than merit). But it’s an arresting, engrossing experience all the way through, full of fascinating nuances, strong performances, impeccable direction, and sharply realized ambition. And you don’t need a pair of magical horns to see it, so that’s a plus.

*By the way, the band he plays with, Canadian hard-ska outfit The Brass Action, is totally bitchin’.

**In the interest of journalistic integrity, I should also point out that he has a rather famous pedigree that he’d prefer you not to know about. You can look it up for yourself if you’re curious, but on the strength of the story here I’d say he’s earned the right to his own individual career. But if you look at a picture of him you’ll probably guess it immediately.

|

CHAINSAWNUKAH 2014 CHECKLIST!

The Hunt For Dread October

|

|

| Maybe a tad too undisciplined to be an unmitigated victory, but ambition counts for a lot. Call it A- |

********************************

Of course, these questions about the abyss brings up a kind of uncomfortable question for us Chainsawnukah-goers, as well. Is that abyss that we should take care not to stare deep into… to be found in fiction, too? Is it possible, like Margaret Thatcher thought, that by watching XTRO or HORNS or FACES OF DEATH that we might really be turning ourselves into those very monsters we so enjoy watching?

I mean, nothing pisses me off more than genre fans defending their violent, exploitative filmatic fetishes by claiming that it’s just art, it doesn’t hurt anyone. Bullshit. All art affects you, that’s the whole point. It’s not just a bunch of colored pictures that moves around in front of your eyes and then go away, the whole point, the only reason to make art at all, is to connect with people, to share something new. And that change, that transformation, is inherent in any new experience you have, and the more powerful that dialogue, that experience, the more extreme the transformation may be. Today you are not the same as yesterday, you have a day’s worth of new memories, new facts, new ideas, new emotions, new experiences. And art strives to cultivarte a particular experience for you to wander in, to imagine something which may be altogether different than your ordinary life. All art is transformative, just as all experience is transformative. And inevitably, sometimes those experiences change people for the worse.

That’s not an argument for censorship, of course, far from it. But it’s something which needs to be acknowledged. We make art in the hopes of changing people, of putting a little of our own particular experience into their brains, shaping them, at least in the moment of the art itself. Sometimes that can have an unexpected effect, sometimes by sharing our own little imagined abyss, we might well be able to turn those who look into it into monsters. But it is not, and it must not be, the responsibility of the artist to try and anticipate every possible interpretation on the part of the viewer; just as art is the shaping and directing of a particular experience by its creator, the experiencer is him or herself bringing with them a lifetime of their own thoughts, biases, history, cultural, personality. It is the experiencer who will undertake the final transformation, try and incorporate this new bit of life into the ever-increasing complexity of the puzzle that makes up their own psyche. It’s up to them to take it and contextualize it, give it its own unique meaning and flavor.

As I talked about last year, discovering horror was just such a transformational experience for me, personally; facing horror, directly addressing my fears about life and death and the terrifying fluid nature of the human experience was indeed a crucible of destruction, but one from which I’ve been able to grow back, rebuild, stronger, better, hopefully to some degree wiser. Destruction is always an element of transformation, and as frightening as it is to experience that sensation of unfixed freefall, there’s something even more awful about stagnating, stunting, rotting from the inside to avoid changing on the outside. But not everyone will have the same experience. You can never truly grow without some level of destruction, and that destruction can sometimes be painful, can sometimes be so total that rebuilding completely may be impossible, or so daunting that working up the strength so do so seems an impossible task. Art can hurt people, I wonder if almost by definition all great art is powerful enough to damage. But if art can hurt people, it can do so only because of the transformational power of experience, and hence, so can life. And life is meant to be lived, not hidden from.

So I say, it’s not just the abyss you need to be afraid of. Those who pick daisies should also look to it that they do not become a monsters. There’s a lot of good in this world, and a lot of bad, and a lot of time and complexity for them to become inextricably tangled. The deeper you look, the more you see, the more of both you’ll encounter, and the stranger and --often-- darker the world may become. Those Horns that Ig acquires here don’t change the world, they merely reveal things about it that we’d often rather not know, and others would certainly rather not share. Is not the apple that the snake bids Eve eat, in fact, the knowledge of good and evil? Is the abyss we fretfully stare into, in fact, simply the truth? Simply a reality which can be so crushing we don’t know what to do but lash out, become the very monsters we fear? The devil is in the details, they say -- I suppose that makes the angels in the elusive and intangible abstractions. But the abstractions are for the angels only; in this real world, there are only devils, seekers or knowledge and truth even in the face of sometimes overwhelming pain.

But even with that, even seeing the world starkly, even knowing that we will forever be changed by what we encounter-- what choice do we have but to press on, aware of both the world and ourselves, and trying, desperately trying, to each day build our new self into something that reflects the best of us, rather than the worst. If HORNS has a moral, it must be that: Even when you are cursed to see the worst parts of life, even when you are helpless as to what others think of you, even as you are powerless to stop the world and its people from inflicting pain and cruelty and banality -- you are still you. You still have power over yourself and your own mind, and you still have a choice as to what you will be, moment-by-moment. There’s angel and devil in us all, and maybe neither one is wholly bad, they’re both a necessary reaction to such a strange life as this. Just as an unwieldy but engrossing horror/comedy/mystery/religious meditation is.

As for me? I choose to watch more horror movies next year, and think even harder, and write even better about them. But, ahem. Shorter. Sometimes the process of building up requires a change of strategy or two. Don’t need a pair of magical horns to see that one, either. May Chainsawnta Claus bless us, everyone!

Happy Chainsawnukah everyone, and see you soon for a much-delayed return to movies you might actually be interested in watching!

Finally. Jesus.

ReplyDelete