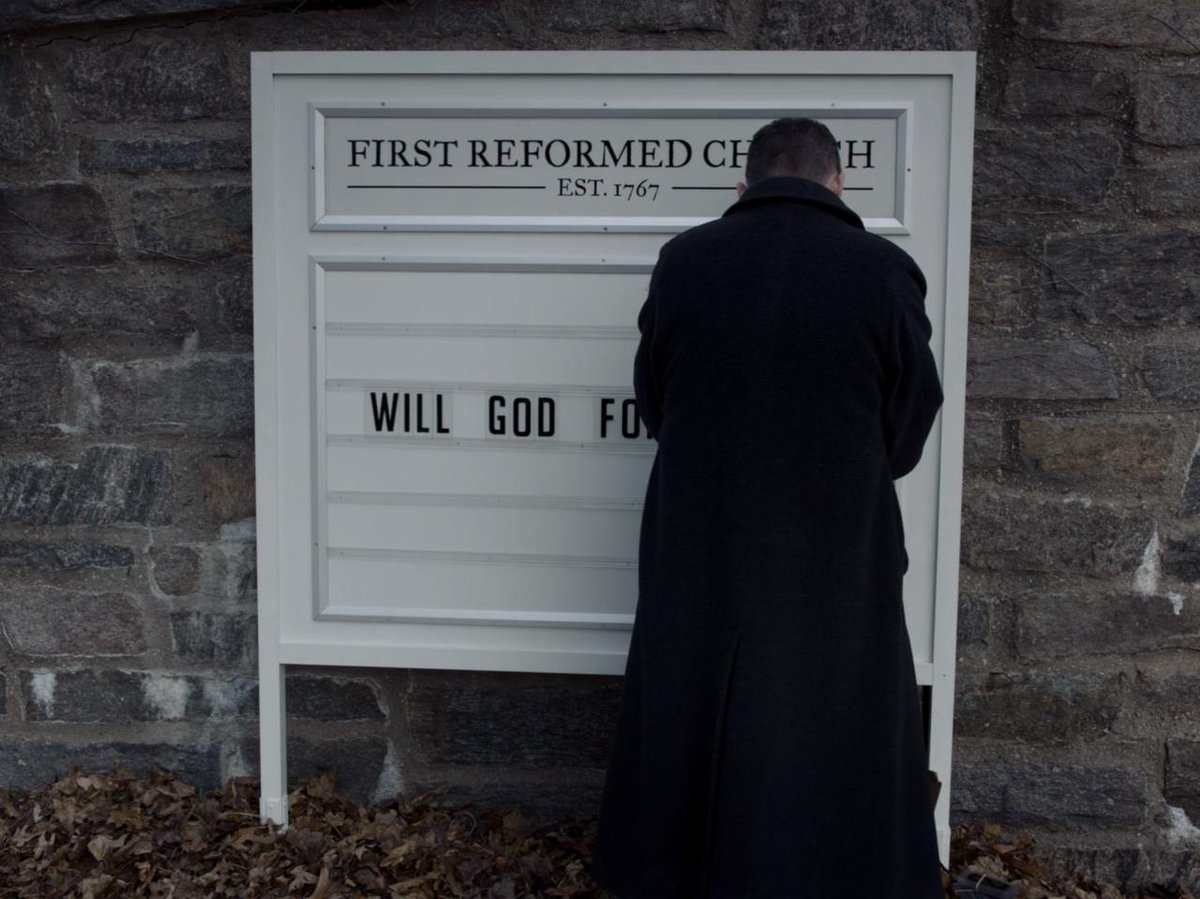

First Reformed (2018)

Dir. and written by Paul Schrader

Starring Ethan Hawke, Amanda Seyfried, Phillip Ettinger, Cedric Kyles

I honestly don’t know if this is a good movie or not. I think it is; I can definitely pick out things about it which are very finely crafted, aesthetically smart. But frankly I’m just too close to it to be able to objectively talk about it like a piece of art. More than any other movie I can think of in recent memory, maybe more than any other movie I’ve seen since I was a teenager, FIRST REFORMED feels like a movie about me, a movie which captures the world as I see it, which tries to wrestle with the particular horror of modern existence as I experience it. It is as close to seeing my own mind on-screen as I have ever experienced in a movie. If it has flaws, they are also to a large degree my flaws, and if it has strengths, they are to a large degree my own as well, at least intellectually (and the movie is almost exclusively interested in the intellectual). To give it any kind of objective evaluation would be to appraise my own mind, a task which, much as I wish it were otherwise, I am uniquely ill-suited to attempt. Suffice to say, then, that I found the experience of watching FIRST REFORMED absolutely shattering, and, perhaps selfishly, I think you might too. At the very least, if you watch it you might understand a little better who I am. That may not be much of a recommendation, but it is the one thing I can offer with any real certainty.

I am not, like FIRST REFORMED protagonist Ernst Toller, a priest, nor, like writer/director Paul Schrader, a Calvinist. But I am very much Ethan Hawke. Not literally, of course, but I identify with the actor in a way which is very unusual for me. Despite being an American male of European ancestry, I’m an odd duck in a lot of ways, and don’t frequently see much of myself* in fictional characters. When I do, I tend to see the worst in myself rather than the best (the pathetic, self-sabotaging grifters of BUZZARD, the delusional, desperately needy Chuck Barris of CONFESSIONS OF A DANGEROUS MIND). But in many of Hawke’s characters over the years, I saw at least aspects of my better self that I encountered nowhere else. Being about ten years older than me, he was playing teenagers when I was a teenager, which is, I suspect, the period of life when we’re most apt to look to fiction for versions of ourselves, or at least ideals of what we could aspire to. Suffice to say, at a crucial moment of my development as both a cinephile and a person, Hawke embodied the kind of cool I wanted to be: intellectual, passionate, edgy, troubled. He combined the sort of rebellious, independent spirit that late-gen-Xers like me were drawn to, but tempered with an intellectual seriousness, a restless sense of curiosity about the world and an eagerness to experience it, that I found uniquely well-suited to own sensibility and aspirations. I was never going to be Sylvester Stallone, but cultured, thoughtful Jesse Walters from BEFORE SUNRISE? Maybe. Hopefully. Someday. At any rate, here was a character, and an actor, in whom I could see, if not myself, at least the self I wanted to have.

And these years later, I still find a lot to admire in the actor. He’s had an interesting career, eschewing the easy mega-stardom that was probably within his reach in favor of more eclectic roles, from Richard Linklater experiments (BOYHOOD, WAKING LIFE) to gritty crime flicks (TRAINING DAY, BEFORE THE DEVIL KNOWS YOU’RE DEAD) to straight-up genre fare (DAYBREAKERS, SINISTER), and in all this time I’ve never once seen him phone it in. Highbrow, lowbrow, he is a rare actor you can always count on to give 100%, even in something as ridiculous and schlocky as 24 HOURS TO LIVE or the MAGNIFICENT SEVEN remake.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/59842357/firstreformed1.0.jpg)

I bring all this up for two reasons: first, as far as I’m concerned, it’s always a good time to remind the world that Ethan Hawke is a God damn national treasure. Second, and more germane to the topic at hand, I feel it’s necessary to emphasize the degree to which he has remained stable my whole life as perhaps the only celebrity who represents a kind of person who I could meaningfully aspire to be. Because in FIRST REFORMED, we find him again playing a character with whom I identify to a striking degree. And that’s a real problem for me, because Schrader considers this film to be part of a loose trilogy, along with TAXI DRIVER and LIGHT SLEEPER. Those are great films, but not films featuring protagonists that anyone sane wants to personally identify with.

Of the three, FIRST REFORMED’s Reverend Toller initially seems the odd man out. He’s got a stable (if somewhat austere and limited) life, working as a priest in a 250-year old New England church which is attended by a few parishioners, but mostly exists as historical landmark. Toller takes his liturgical duties seriously, but it’s clear his role as a priest is largely symbolic, and he’s really being retained as a caretaker and tour guide (his responsibilities include stocking the gift shop) for the old building, which is owned by a nearby megachurch and is itself primarily used for symbolic occasions, one of which is the building’s upcoming 250-year anniversary. Though Toller is outwardly functional, his obsessive journaling reveals that internally he’s a miserable husk, languishing in a self-imposed exile from the world as penance for pushing his son into the military, where he died during the Iraq war. Struggling with alcohol and hopelessness, Toller has been desperately, obsessively searching arcane religious writings for… something. Some reason to hope. Something to believe in. Some way forward. But he can’t make himself believe any of it.

His quietly imploding world of personal despair is interrupted by someone looking to him for the very thing he can’t seem to find for himself: hope. That would be Mary (Amanda Seyfried, JENNIFER’S BODY) the pregnant wife of environmental activist Michael (Phillip Ettinger, COMPLIANCE, BRAWL IN CELL BLOCK 99), a man so pessimistic about the future of the human race that he thinks bringing a child into a world of such dismal prospects is in itself an amoral act. Mary hopes Toller can talk him out of his bleak worldview, and though Toller doesn’t think he’s up to the task, and even suggests she might be better off seeking help elsewhere, he reluctantly accedes to talking with Michael. Unfortunately for him, Michael’s despair is very much rooted in hard fact. He’s spent his life trying to save the world, only to see it sink deeper and deeper into ruin in ways which are specific and quantifiable. He has graphs and charts, a mountain of data that supports his prognositations of doom. Toller is an intelligent guy with the usual stock of religious apologia, but as much as he enjoys this rare opportunity for a lively intellectual discussion, he privately knows that Michael is right, and there’s nothing, ultimately, that he can say to overcome the simple fact that all available evidence seems to point to despair as the most logical reaction.

And this realization –or perhaps, this crystallization of what he already knew, on some level—inexorably pushes Toller to think about his own role in all this. And a problem of this dire scale is a dangerous notion for a man with nothing to lose to dwell on.

This scenario, then, has, in some ways, a very similar shape to Schrader’s most famous and celebrated screenplay, 1976’s TAXI DRIVER: again, you have a guy with nothing to anchor him to society faced with an infuriating injustice that the world seems incapable of even noticing. But there’s a key difference between them, and it’s the heart of why this movie was so particularly shattering to me. It is, simply, that Michael, and subsequently Toller, are simply right. TAXI DRIVER’s Travis Bickle is a psychotic, a deranged obsessive outsider whose fixation is rooted in his own alienation, and spurred by the perverse extremities of human corruption which transform the world around him into a lurid grotesquerie. But Toller isn’t any of those things, and his world is a much more mundane, veristic one. He’s depressed and guilt-ridden, but there’s no question that he’s also a functional adult, a thoughtful, intelligent guy not in any way inclined towards cheap fanaticism or radical destructiveness. And the villains of his story are depressingly banal; they’re not exaggerated monsters, in fact their very evil flows from how reasonable they are, or at least believe themselves to be. Toller’s boss at the megachurch (Cedric “The Entertainer” Kyle[!], THE ORIGINAL KINGS OF COMEDY) is a well-meaning, friendly guy who seems to genuinely care about Toller’s well being. But he has a huge organization to run –an organization that likely does a lot of real good in the world!—and it needs funding and structure, and that means cooperating with, rather than challenging, the avatars of social and economic power. In fact, doing so looks like sanity to him, looks like what a reasonable, responsible figure of authority ought to do. And that means Toller’s stubborn, disruptive moral crisis looks like instability, if not outright derangement. And the truth of it is, it is instability; it’s exceedingly inconvenient for someone so invested in the system to have some kind of earnest idealist poking at its foundations. But Toller isn’t crazy; he’s unhappy, isolated, unstable… but he’s sane. It’s the world that’s insane. And in an insane world, a truthful, sane response looks like madness.

I mean, let’s just talk it out, here, shall we? We have a moral imperative to future generations, to the continued existence of life, right? And if we encounter people actively and selfishly working to destroy that future, we have a moral obligation to oppose them, right? And if they use their ill-gotten bounty to seize power and prevent us from opposing them within the system they can set up and manipulate to their advantage, our moral obligation doesn’t simply end there, right? We still have a moral obligation to take action to affect real change, to do everything which is within our power, especially in the face of a scenario as grave as the current one, right? Even potentially at the cost of our own lives? If there’s a moral argument that lets us off the hook, I’ve never heard it. And yet, this logic has led us to some extremely troubling possibilities. If we follow the values we claim to believe in, it brings us inevitably to somewhere we don’t want to go. But if we shrug them off and tacitly admit that we never really believed in them to begin with, what does anything mean?

That’s the thing about FIRST REFORMED which, at least to me, feels so gutting. I can’t think of another work of art which feels so honest about how hopeless the world is. Which is to say, there are plenty of dismal, hopeless movies about the inevitability of suffering, but this one comes by that hopelessness is a uniquely intellectual way. There is no obvious weakness in Toller’s logic, there is never any point where you can argue he’s missed something or has other options. (vague SPOILERS follow) If he believes what he professes to, then the only two options are either the one he takes or the one Michael takes; the “best” option the film offers, and the one it ends on, is maybe he just gives up and tries to live a happy life and not think too much about the stuff he claims to believe in. (End vague, minor SPOILERS)

In short, any sort of intellectual honesty about our responsibilities to the world leads to a miserable selection of impossible solutions. It’s the perfect microcosm of the inescapable dismal logic of my life so far, and the reason I don’t know that I’ve ever seen a fictional character that I so profoundly saw myself in. I’ve struggled with this very dilemma myself, and my continued existence is less a testament to my successful moral reckoning than my cringing willingness to dodge these questions and retreat back to the simpler comfort of living my own small life. But that solution comes with its own sort of fatalist emptiness, a willed myopia in the face of total hopelessness that anything can be done to save humanity from itself. We’ve come too far, it’s too late now. This gets worse and worse from here, and all we can do is watch it all fall apart and try and cling to our tiny lives and try to put it out of our minds as much as we can.

****************************

(END SPOILERS FOLLOW – read only once you’ve seen the movie) And indeed, it’s on that very note of dissatisfying uncertainty that the movie ends. And it’s an appropriately jarring ending which suddenly swerves away from the fatalist TAXI DRIVER climax it seems to be headed towards, instead settling into something much stranger and more mysterious. It builds to the perfect apocalyptic pitch of inevitable tragedy… and then, suddenly, a little glitch throws the whole thing off. Toller has gone too far now to turn back, and yet suddenly he can’t go forward. It’s a beautiful evocation of how life can disrupt our plans, even when we’re at our most certain.

(END SPOILERS CONTINUE – read only once you’ve seen the movie) I mean, as upsetting as Toller’s solution is, it’s also very much a relief to him; he’s miserable anyway, and this is a chance for an escape as much as it is a strike against the evil of the world. He’s finally at peace, he finally has purpose, finally has some hope that he can do some good. And then, just as he’s reached the point of no return, the situation shifts and he finds his certainty that he’s doing the right thing colliding head-first with his deep care for another person. It’s an absolutely irreconcilable situation; his conscience won’t let him do what he was planning, and yet it’s the only thing left that he can do. The only thing to survives that paradox has nothing to do with philosophy or conscience, it’s just his simple instinctual need for human connection. Something innate, immediate, physical, far removed from both thought and consequences, but no less inescapable, though it’s something he’s spent the whole movie trying to escape. It’s strange and awkward and confounding, and that’s just how life is. Certainty is easy, but life has a way of turning your most ardently held philosophy into hopeless chaos.

(END SPOILERS CONTINUE – read only once you’ve seen the movie) Which brings me back to my own life again – a selfish thing to do in a movie review, I know, but something I can’t bring myself to avoid in a movie which feels this personal. I’ve always used this blog as more of a journal than a catalogue of artistic merit, and with this particular film there’s no escaping it, my reactions are too intrinsically linked to my own struggles to separate them out and pretend this is in any way an objective discussion of a film. I relate so intensely to Toller’s philosophical free fall because I’ve lived it. I think I can say without false modesty that I’m a guy who desperately wants to do the right thing (regardless of how rarely I manage to do so), and that the only approach to that goal that I ever understood or related to comes through rigorous intellectual inquiry. Other people relate to things more empathically, and I think that’s good and necessary, but it’s not what I’m equipped for. Rational analysis is the only way I know to make sense of the world and how we’re supposed to live in it. I think Toller would probably describe himself the same way, and that’s why I see so much of myself in his complete disarray at the end. When a person like this follows what seems to be an irrefutable logical argument to a conclusion which gives you a rare sense of certainty and purpose, only to find that it brings you to an impossible, unworkable scenario… it’s destabilizing on a level that’s hard to even describe. I suspect it’s somewhat akin to suddenly losing your deeply held religious faith. You go through a period where everything feels like some kind of giddy, nonsensical dream. You feel panic, desperation; every action you take feels random and out of your control. You want to die, you want a sign, you want something to resolve it all, you crave that apocalyptic sense of self-destruction that was going to wrap everything up so neatly.

But nothing ever comes, and then you just keep waking up every morning, and finally you have no choice but to do the hardest imaginable thing, which is to just keep living. The end of FIRST REFORMED is the best portrayal of that mental journey I’ve ever seen on screen; it captures the abruptness of it, the frustration, the uncertainty rushing back in all at once, and, most of all, it captures the infuriating open-endedness of a desperate question which doesn’t have an answer. When you find out that you’re actually going to have to live, even though you don’t want to and don’t have any clue what you’re supposed to do about that. It’s strange and disorienting and awkward and beautifully unfinished.

***************************

Very few works of art can support a vision that bleak, and almost none ever try to reach that emotional point through intellectual rigor instead of emotional manipulation. I doubt it’s the best way to reach most people, but to me, watching this felt like having my guts ripped out. And yet, I’m not sorry that I did. It’s a relentlessly miserable, despairing film, and yet I emerged from it feeling oddly comforted. In a funny way, as hard as it was to watch, I felt a little less alone after seeing it. I’ve already been through this, lived through it, fought through it, maybe even self-indulgently wallowed in it. I know this terrain intimately and deeply. My demons are already all-too-aware of the litany of despair which FIRST REFORMED inventories, and they emerged from the experience without any fresh ammo, but perhaps somewhat cowed to be dragged out in the open with such vividness and empathy. Neither Paul Schrader, Reverend Toller, nor I have managed to wrestle an answer out of the hopeless paradox of existence, but having fought through it with them, I feel a certain spark of camaraderie. If I still don’t understand, there’s a certain succor to at least feeling understood.

*Which should by no means be taken as an argument against greater diversity in film; if anything, it should be read as an argument for more. Thousands of cis white male actors and I still find it astonishing when I see one who I actually feel some personal identification with. Imagine how a trans Indonesian plumber or someone must feel! We need more stories told!

Heh, yeah. This one was immediately personal. It actually felt a bit good to watch it, as in processing the overwhelming, curse-like struggle I experience living right now. And hey, lookie here, it's not a curse - we're not alone in this.

ReplyDeleteOn a good day, I live with all of this as with mortality. Gotta come to terms with it and it's motivating me to act kind and be present. The bad days come, but they end too.

Take care, still love to read your stuff.

Thanks Maciek, it's always good to hear from you!

Delete