Pane e Tulipani (Bread and Tulips) (2000)

Dir. Silvio Soldini

Starring Licia Maglietta, Bruno Ganz

Bread and Tulips is the kind of movie I don't watch very much. It's a straightforward little Italian drama/comedy about love, responsibility, travel, fulfillment, being a florist, and so on. It's one of those movies that you know is going to be well-made and entertaining, but just can't get too excited about in a world where there exist movies about giant robots, lesbian vampire covens, 3D cave art, etc. There's a certain demographic out there that loves this type of film, but to tell you the truth I bet not a lot of them watched it. Because that demographic is "people persons" who typically can find the company of actual people and hence eliminate the need to drink cheap scotch and watch Z-grade horror movies alone on a Friday night. This is the kind of movie that requires that you're interested in the characters and their feelings, and that's not the easiest sell in the world.

So I don't watch this sort of deal that much. It's not particularly alluring to my usual filmatic inclinations, nor is it artistically or historically interesting enough to pique my interests. Just a simple little story about a nice lady who comes to a crossroads in her life with the help of a few likeable quirky characters.

If it was an American film, it would be one of those obnoxious rom-coms with the shrill comic relief and the gorgeous big-name stars barely even pretending to be older and burnt out. But being a foreign film, it doesn't seem quite as desperate and gaudy. Its a little slow, a little sad, a little quiet, a little surreal. It's not about young people or beautiful people, there's no twist, not much at stake. Its got some laughs but its not desperate to get a laugh every few minutes. It's even OK with a little moral ambiguity.

Basically the story is this: Rosalba (Licia Maglietta), A housewife with two teenage kids and a husband in the plumbing supply industry gets mistakenly left behind on vacation, HOME ALONE 2-style. It's an honest mistake and she's not super mad about it, but its just irritating and insulting enough that she decides to leave the family hanging and hitchhike home. This one small act of independence and selfishness sparks something in her. Something small and quiet and unfocused, but rebellious enough to take control of her and send her to Venice (motto: "Non preoccupatevi il nano nel cappotto rosso" ["don't bother the dwarf in the red coat"]), where she's never been before, without much money and without a clear plan except to not go back home quite yet.

She ends up staying with this lonesome handsome mysterious gentleman with a charmingly formal way of speaking, so we can all see where this is going. But in some ways, its kinda fun to see a basic romantic comedy plot which is set in something like the real world and takes its characters seriously. There's a scene early on where our heroine unknowing disrupts her housemate's attempt at suicide by hanging. Bet you won't see that in the American remake.

The remake would also insist on making the family she's leaving behind a bunch of nasty ingrates who learn to appreciate her only when she's gone. I like that this version (I'm preempting the inevitable remake by just calling it the “original” version) doesn't really play up that angle. It's true that her family doesn't really appreciate her, but then again she doesn't much appreciate herself either-- or have much going on-- so its easy to see why. When she's gone, they're perplexed and a little annoyed, but not more than is reasonable. They're inconvenienced but they get on with their lives about as well as you could expect them to. The husband's kind of a blowhard but not cartoonishly so; he's pretty much got his life set up the way he wants it, and is mostly confused that suddenly his wife has other ideas about what she needs for herself.

This shifts the blame, slightly; the problem isn't that Rosalba is under appreciated, it's that she doesn't appreciate the life she's living. Not that she has any reason to, but it's not like that life was forced on her. She's been drifting through her life going through the motions and never asking herself if it was good for her or not. Now, she wants a chance to figure out who she really is and what she really wants, but things are complicated by the fact that she's got a whole life of responsibilities already. It's kind of the other side of KRAMER VS. KRAMER. Actress Maglietta tells most of the story with her face, which has the odd look of someone who could be interesting but hasn't been interested in anything in a long time. It's the look of someone waking up from a dream and gradually becoming aware of the world again, and it gives the movie a solid foundation of quiet excitement instead of bitterness at time wasted.

The film's ace, though, is Giuseppe Battiston as a nebbish plumber who the husband hires based on the “hobbies” section of his resume. He's an avid reader of detective fiction, and hubby figures he'll work cheaper than an actual detective to find out what the heck his wife is up to in Venice. Battiston plays it a little broader than the rest of the film, but he's a hoot as he takes to his new detective role by chain-smoking cigarettes in a trench coat, hat, and dark glasses (even the cinematography subtly changes to emphasize his noirish aspirations). It's a funny concept which plays out pretty perfectly and adds some levity to things.

Anyway, there's not a lot here; she has some small but meaningful experiences, learns a little about herself, meets some quirky characters. That plot could and does describe plenty of terrible movies. But this happens to be one which does that plot thoughtfully and with some careful but not flashy craftsmanship. It may not be the easiest sell to a guy like me, but I gotta admit I enjoyed it. Probably worth watching this kind of thing from time to time, if only to be reminded that sometimes all you need is a person with an interesting face and a little time to figure herself out.

PS: Nicholas Roeg was right, though, off-season Venice is creepy as fuck. Luckily the film doesn't try to play it up as some romantic icon, but I don't know if it's intended to come off quite as much like a post-apocalyptic ghost town populated by delusional psychotics. It does give the film a kind of surreal quality, though, which keeps it from getting too cloying.

Friday, May 27, 2011

Thursday, May 19, 2011

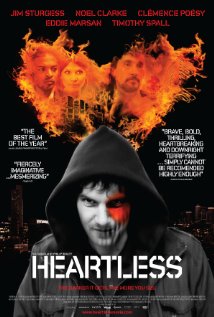

Heartless

Heartless (2009)

Dir. Philip Ridley

Now he's a movie full of great ideas which seems competently made and yet somehow manages to bungle each and every one until it ends up feeling almost completely empty. How the fuck did that happen?

The premise seems like exactly the sort of thing I'd be into. Netflix says:

Reclusive Londoner Jamie Morgan (Jim Sturgess), who bears a prominent, heart-shaped birthmark on his face yet can't seem to find love anywhere, makes a deal with a devil-like figure to get a girl [who turns out to be Harry Potter's Fleur Delacour, by the way, if you were ever interested in seeing her naked]-- but there's a deadly price to pay. After his mother is murdered, the newspapers say thugs wearing devil masks committed the crime. But Jamie soon begins to suspect that they weren't wearing masks at all.

So that sounds pretty cool, right? Guilt, disfigurement, violence, paranoia, the slippery divide between what's real and what isn't. That sounds exactly like the kind of shit I'd be all over, kinda Cronenberg-y back when he was a little more surreal, or maybe like if David Lynch made a movie with a plot. Except it doesn't play out like that at all. All those elements are in the movie, but for whatever reason the movie focuses on exactly the wrong things in the wrong order, playing up the exact least interesting things and barely touching on the promise of that premise.

For starters, the film is disappointingly literal. That dreamlike quality that I so covet in a movie like this is completely undermined by the fact that the film doesn't really tease us at all about the demons being real. It shows us one about 5 minutes in, and never backs off the idea that this is literally some supernatural shit going down. As a result, you lose the scary ambiguity AND the apocalyptic sense of a collapsing society. This would be fine if you played up the scary supernatural angle, but instead they continue shooting it as if it were a gang running around. There's nothing done to make this concept seem otherworldly or incomprehensible; Its just a bunch of skinny demons in hoodies attacking people with molotov cocktails. It's LESS scary since demons are so one-dimentional; of course they're gonna be malevolent. That's their gig. Human killers are scarier and more interesting. You got a bunch of murderous human hoodlums running around, you got to ask some uncomfortable questions about what you are capable of, how they ended up this way, etc. Demons don’t work that way; they’re scary when you see their nonhuman power and characteristics, which this film largely robs them of. So right off the bat, a huge part of what could be interesting and frightening is rendered somewhat flat and diminished.

Secondly, the whole Faustian bargain thing is ill-handled. The devilish Papa B is obviously supernatural, but they mostly avoid giving him any kind of mystery. He’s played pretty much like a mid-level thug in a Guy Ritchie movie, all muscles and mullet and exposition. There’s nothing perverse or disturbing about this guy; he seems more like a wannabe Tyler Durden than the devil incarnate. His plan is to cause chaos because suffering is eternal or some stupid trite bullshit like that. So again, you’ve got this potentially creepy, weird scenario which is just completely undercut by making everything seem very literal and overexplained. Even Papa B’s cool-looking SILENT HILL apartment looks diminished and literal. Director Ridley shoots it like he’s shooting a regular conversation in a normal apartment, and as a result it all looks sort of normal and solid, like a cool set instead of like the inside of a nightmare.

|

| (on the other hand, I'm of the opinion that SILENT HILL didn't have enough comfy green armchairs, so this one addresses that issue nicely). |

Which is not to say that it’s badly shot, either. It looks, like everything in this film, competent, professional, even a little stylish. It just doesn’t cater to the film’s strengths and as a result, nothing has the impact that it should.

There’s a ton of crap like that in here. The film somewhat boldly subverts the usual Faustian bargain business by suddenly changing the rules on our poor protagonist. It’s a cool idea which could serve to throw the audience off balance and make them feel vulnerable and out of control. But nothing particularly shocking comes out of the new scenario, and without clear rules for the universe we actually don’t know what to fear and consequently lose tension, rather than gain it.

The real dealbreaker here, though, is that the film is ultimately much more about the human drama than the horror. That would be fine, except that the human drama is laughably vapid. Jamie has to realize his true beauty was within, and there’s some insufferable crap about his father telling him that the darkest moments are the ones we learn the most from which in context doesn’t even make sense. It’s all very shallow, and worsened considerably by the fact that it’s all done with the subtlety of a shotgun blast to the face. Again, you can’t help but notice that the film focuses on the least interesting aspects of the story (and in fact, the whole demon angle ends up feeling kind of incidental. You don’t need a gang of eyeless demons to tell the story of the ugly duckling. I guess if you’re going to do a live action version of that story, adding demons is the only way to go, but fuck, kind of a waste of perfectly good demons.) All good will is ultimately killed by the end, a standard twist that you’ve probably guessed already, which pretty much makes everything before it kind of confusingly meaningless.

|

| I know, I know, it looks cool. But trust me when I'm tell you it's the demon equivalent of big fake titties. |

Which is kinda a shame, because the elements for a great film are there. The usually bland Jim Sturgess creates a surprisingly memorable, sympathetic character and very effectively sells his painful shyness. He’s a clenched up recluse, perpetually waiting for the next cruel blow to fall, and Sturgess remarkably shares his crushing internal pain with the camera. The great Timothy Spall fiercely attempts to impart some truth and conviction into his cliché-ridden flashback scenes, and Eddie Marsan has a dryly memorable cameo as the workaday administrator for Papa B. Though criminally underutilized, the production design is great, the demons are neat-looking (would have been 100 times cooler had they been masks instead of CG, but oh well) and there’s a few memorably horrific scenes (including one genuinely shocking one featuring a reanimated severed head who finds that things can get even worse).

In the end, though, this is a story of squandered potential. Fear lies in the unknown. The more you explain, the more you show us, the more you tell us what’s going on, the less darkess remains for fear to lurk in. HEARTLESS is a film so eager to make sure we understand what it means that it loses sight of the elements that make the journey worthwhile. It has its own magic tricks, but right away it wants to explain how they work, and -- even more damningly -- why the trick was done. We want to see the trick, Ridley – you can leave the rest to us.

EDIT: SPOILERS! Oh yeah, I wanted to mention that early on there's this weird awkward exposition on TV about this crazy looking gang leader with some sort of elaborate golden claw for a hand. Inexplicably, he's named "She" (he's a beefy black guy with facial tattoos). But it's clear that (S)he is the leader of some other gang, not the demons. Well, since they made such a big deal about it you figure it's gonna come up again later, and it does. Jamie is in his place of business with his nephew, who owes money to a gang (long, pointless story) when suddenly She comes crashing in and attacks Jamie, who promptly stabs him to death. And he just goes, "oh, I guess I killed She," and runs off to be pursued by the other demon gang, never to mention it again. And that's it! What the fuck was that all about? I get that being named She is probably even worse than being named Sue, but what's with all those weird details? Maybe this thing is deeper than I gave it credit for.

|

| A "flawless" "horror"... the "best" film of the year. |

EDIT: SPOILERS! Oh yeah, I wanted to mention that early on there's this weird awkward exposition on TV about this crazy looking gang leader with some sort of elaborate golden claw for a hand. Inexplicably, he's named "She" (he's a beefy black guy with facial tattoos). But it's clear that (S)he is the leader of some other gang, not the demons. Well, since they made such a big deal about it you figure it's gonna come up again later, and it does. Jamie is in his place of business with his nephew, who owes money to a gang (long, pointless story) when suddenly She comes crashing in and attacks Jamie, who promptly stabs him to death. And he just goes, "oh, I guess I killed She," and runs off to be pursued by the other demon gang, never to mention it again. And that's it! What the fuck was that all about? I get that being named She is probably even worse than being named Sue, but what's with all those weird details? Maybe this thing is deeper than I gave it credit for.

Saturday, May 14, 2011

Creature from the Black Lagoon

Creature From The Black Lagoon (1954)

Dir. Jack Arnold

Would you believe I'd never seen this one? I never really made an effort to watch all the classic Universal Monster films, but they tend to be the sort of things you just encounter. Watch DRACULA in a double feature with FREAKS, see WOLF MAN in a film class, check out FRANKENSTEIN on TV while sick from school as a kid, you know. Films with this level of clout just find you. You need to go out of your way a little to see HORROR EXPRESS. THE MUMMY (1932) just comes to you. In my case, I watched it standing in a long line to enter a haunted house one Halloween with my mom. That's what happened to you, too. You never decided it was time to watch it, but at some point you just did. It found you. These films find you, somehow.

Except for some reason, this one didn't. And as of 11:43 PM on Tuesday, May 10 2011, I was done politely waiting for the Gill-Man to make its way to me. I took the fight to it. Just like Gill-Man would do.

Well, I'm glad to have seen it, but this one is definitely in the lower tiers of the loose Universal Monsters series. Filmed in 1954 in 3-D, (apparently only the second Universal film to be released in 3-D) it is also among the last of the series (most of the biggies, such as MUMMY, DRACULA, FRANKENSTEIN, and THE INVISIBLE MAN were released nearly two decades earlier). It has plenty of the cornball qualities you probably expect from this era, but unfortunately lacks a lot of the artistry which pushed most of those films to classic status.

For one thing, it lacks a strong central performance which helped anchor most of the great monsters. Bela Lugosi, Boris Karloff, Lon Chaney, Lon Chaney Jr. and their ilk were not just beneficiaries of great monster makeup; they were magnetic personalities with classic takes on these characters which redefined them for subsequent generations. They were the charismatic lynchpins upon which the whole film rested. By this time, the formula is well-established and director Arnold clearly understands that the creature is the star. But Gill-Man, despite his cool design, is a bit of a cold fish. Ahem. He's a cipher without much to relate to, character-wise. He's cool and menacing, but he unfortunately doesn't provide much pathos or drama, and without that you're forced to rely on the human characters for some sort of story arc, and you can imagine about how well that works. The characters and their stories are so perfunctory that it honestly isn't even worth explaining the plot and who's involved. They're a couple scientists who end up in the Black Lagoon, and that's the only relevant thing. But since they can't really hang any drama on the creature, we have to endure quite a bit of time with placeholder characters that barely even make an effort.

But the way they prattle on about this and that, you sort of get the idea that the film might just be about something. That the creature has endured this long, and in the lofty company he is associated with, can only be testament to the fact that something about this concept connects with people on a slightly deeper level. The reason these classic movie monsters persist is that they don't merely represent bodily harm. The monsters themselves represent something more psychological deep-rooted fears about our world, and often fears about ourselves. Vampires, of course, represent human sexuality and desire - so much so that they've gradually lost most of what made them monstrous as our society finds itself a little less terrified of human desire (for the record: I'm pro-desire, but if we have to trade Bela Lugosi for TWILIGHT to get a less judgmental society I say it may be time to bring back those stylish scarlet letters). Werewolves represent the frightening and painful bodily and emotional changes undergone in puberty. Zombies (a la their Romero reinvention) represent our insatiable consumer culture. Frankenstein represents our fear of loss of identity and meaning. And so on. Most of the classic monsters could (and do) have whole books written about their symbolic meaning and the way that meaning has become part of our representational culture.

What, then, is our pal Gill-Man telling us about ourselves? I feel that it doesn't read as clearly as the other monsters I mentioned, which is probably a big part of the reason this film feels less effective than some of its predecessors. It doesn't quite go for our subconscious fears with timeless, classic symbolism in the same way. There are no creaking castles or foggy moors in here; it’s a thoroughly modern (1954) movie populated by bold, effective white scientists and simple, colorful locals, and shot mostly in the daytime. I wonder, though, if that isn't sort of the point. These scientists (an ichthyologist, a geologist, a business-scientist and a girlfriend-scientist) are way into talking about the Devonian era, the geologic period during which legs first began to develop and ocean creatures began to venture onto land. Well, you can hardly say "Devonian era!" with a blank face suggesting an unsettling fear that there might be other eras to remember the names of before you start talking about evolution, which is exactly what these scientists do.

Remember, this is 1954, where evolution is not the dry, noncontroversial academic issue which every schoolchild clearly understands that it is today. They don’t talk much about the philosophical implications, but shit, the Scopes trial was in living memory of every one of these characters. And here they are in a black lagoon in the middle of the most unconquered land left in the world, with this weirdly human fish thing which has a suspicious interest in their women. We diverged from this thing as far back as the Devonian era, and yet we have more in common with it than anyone in the film wants to admit (or even monologue about). I suspect that the Creature, if anything, is there to represent the discomfort audiences of the time still felt with the concept that human animals were not quite as different and special as we might like to believe, and that the scary, alien things we see in nature are a far greater part of us and our history than we’re comfortable examining.

Well, like I said, since then we’ve all become completely accustomed to this concept and there’s no debate or discomfort about it at all by anyone anywhere, so the movie doesn’t really work on this level any more. It does, though, perhaps work on a slightly deeper level that the evolution thing only plays at. By being like us without being us, the Gill-Man does indeed represent the things we share with our animal ancestors and our own animal instincts. But unlike the Wolf Man, who also represents our animal urges and desires, Gill-Man represents a different part of our animal brain – the reptilian part, the cold, incomprehensible, instinctual part of us. Gill-Man isn’t warm and furry; he’s alien and unknowable, yet has too much in common with us to dismiss as unrelated to our lives. He’s the nonrational self which we don’t understand and can’t control, too alien to understand but too familiar to ignore. He’s the fear of the unknown self, the part of us deep in the primal psyche (our unconscious black lagoon of primal muck) which is alien to our mammalian emotional and social instincts.

We understand our antisocial impulses; anger, lust, jealousy, hate. We may fear them about ourselves, but at least we can understand them and control them. That’s Wolf-Man Territory

On the other hand, the monster is --of course-- the star here, and the film barely tries to conceal its empathy for the poor misunderstood guy. Our nominal hero (the forgettable handsome, modernist-manly Richard Carlson) spends most of the film convincing his colleagues not to kill it, and berating them when they try (he shouldn’t have worried; the thing takes quite a beating and will be back for sequels long after the names of the main characters here have been forgotten). This sense of a frustrated creature driven by unarticulated feeling and desires but rebuffed by society also, whether intentionally or not, speaks to the kind of people who were watching this stuff then and now: nerds.

Like nerds, the creature lives in an isolated, lonely area where he is uniquely suited. Interestingly, the creature is portrayed by two people: Ricou Browning in the water and Ben Chapman on land. This otherwise inexplicable use of different actors (which continues to each sequel as well, although different actors would take over on land) means there’s a stark difference between the graceful, natural swimming and his awkward, alien attempts at moving on land. Like many awkward loners before him, he has felt moved by feelings he cannot quite put into words to venture out of his comfort zone and try to interact with the handsome, athletic scientists of the world and their girlfriends who he doesn’t quite know what to do with but obviously wants something from. And just like every time this happens, a few people end up getting murdered, everyone misunderstands, spear guns enter the picture, escape is prevented, and everyone flees back to their underwater caves.

I find it hard to believe this was completely unintentional. With almost two decades to learn from the success of the previous monster franchises, I suspect the producers of the film understood that there was a certain demographic which would appreciate and empathize with the monster’s isolation, his inability to make sense of his world and his place in it. Hell, the makers of KING KONG (which features a virtually identical story, without the third act back in ‘civilization’ or anything else which makes Kong’s narrative mildly unique and interesting) understood that as far back as 1933. Here, Arnold and writer William Alland even try to milk that same Beauty and the Beast angle, which works considerably less well here because Gill-Man is much less expressive and charismatic than the id-centric Kong.

That it works at all is a testament to the one thing the film really gets right: the creature itself. First and most importantly, it’s a fantastic design which somehow got made into a truly extraordinary costume. The thing looks great, moves extremely naturally (with the slight exception of the clawed hands which look a little like gloves) and holds up immensely well. They wisely reveal the creature early and nearly all the pleasurable moments in the film come from marveling at how cool he looks.

The second thing that works is the way they shoot him. The movie is generally artlessly made (maybe it looked better in 3-D?) and generally devoid of any effective atmosphere, let alone visual poetry. It does have one single trick up its sleeve, however, which elegantly ties up everything creepy and cool about the concept and execution of the film in one shot. Girlfriend-scientist swims along the surface of the water, bathed in sunlight. Underneath, the creature parallels her swimming in his own wriggly style, watching her from below. It’s probably the one legitimately classic thing about the film, and still packs a punch, both poetically and as great horror staging.

The underwater photography is, in general, cooler than anything that happens on the surface, with the camera taking advantage of the greater underwater mobility to get some effective stalking and even action angles. The suit looks even better under water and actor/swimmer Ricou Browning gives our man Gill a unique, twisting swimming style which looks both unique and very natural – sort of the way a human swims, but not quite (probably most like the way a human swims in a bulky rubber suit, but the effect is good).

All things considered, I’m glad to have seen this one as part of my general cultural edification, but it’s not a film I’m likely to revisit all that often. It doesn’t connect on a gut level the way those older, more evocative monster films do, and despite the striking design of the creature the whole thing, even with its lightly implied subtext, feels sleight and padded. Still, I’m curious about the sequels – the first sounds like a rehash but since its Clint Eastwood’s first film (he plays an uncredited lab technician who has a conversation with a cat, apparently) I may have to check it out. The third one sounds a little more interesting, however – THE CREATURE WALKS AMONG US finds the creature captured and taken to civilization, where an accident causes him to lose his gills and submit to human clothing and study by more scientists and their girlfriends. That one sounds just crazy enough to be interesting, and also sounds like a logical extension of the subtext from the original, which could open some interesting doors. And with a long-promised remake on the horizon (the writers say they’re re-imagining Gill-Man as a product of Man’s poor treatment of the rainforest, an amusingly ill-conceived take considering that it undermines literally everything about the subtext of the original) it looks like this Gill-Man’s got some life in him yet, even if it looks a little awkward and unfocused to us Lung-Men.

|

| Soon. |

Saturday, May 7, 2011

The Man Who Fell to Earth

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

Dir. Nicolas Roeg

Starring David Bowie, Rip Torn, Buck Henry, Candy Clark

When a trusted source first recommended Nicolas Roeg's DON'T LOOK NOW by saying it was the scariest movie he had ever seen and had the best sex scene he'd ever seen, I suspected I was about to find a new favorite. I was not disappointed. And yet somehow I never really followed up on Roeg's filmography. Yes, I saw WALKABOUT somewhere, and eventually saw PERFORMANCE (co-directed by even crazier Donald Cammell) but I never undertook the kind of systematic study that Roeg clearly merits from DON'T LOOK NOW alone. In fact, it appears he's made a dozen films on his own, one as recently as 2007. But of course, it was his classic bit of 70s weirdness with David Bowie that first drew my attention, so let's start there.

THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH is called science fiction (Bowie

Basically, its kind of fun to enjoy the innocence of a time when someone thought you could get people to take seriously the idea that Bowie's home world looks like a bunch of mannequins wrapped in tin foil living in wigwams with wings in the desert and put that image in the middle of a serious, dark dramatic film.

And you know what? You CAN take it seriously, because the filmmakers are good enough that they convey to you how serious they find it. Their genuine lack of modern cynicism and been-there-done-that weariness is infectious, and makes their ambition to try new things honestly feel way deeper and more effective than would be possible now that we know better. Like those corny scene transitions with the on-and-off cuts in EASY RIDER. Everyone loves that shit about the movie, but has anyone ever tried it in anything else, ever? Of course not, because actually it's pointless, distracting, and ugly. But it’s still fun to watch someone try it so optimistically, so hopeful that they're on to something big.

Anyway, if you can step back and allow yourself to enter a world of 70s hedonistic innocence, the movie is pretty great.Bowie Bowie Bowie

There is a story somewhere in the middle of all the style and narrative experiments --Bowie Bowie

ToBowie

In fact, the whole thing is vague and surreal enough that you might even argue that there's some ambiguity about exactly what's really happening. There’s perhaps enough evidence to suggest that maybeBowie

Ultimately, it’s a film about not being able to go home again – whether you’re E.T. or just a lonely, smart, impossibly thin British weirdo. We’re already so alienated that it takes an actual alien to try and articulate that deep, crushing loneliness seem explicit or worth remarking upon. Roeg has an unusual gift for finding the unseen costs to the soul and making them seem heartbreaking all over again. Here, he cleverly disguises an examination of universal youthful alienation in a story which seems safely removed from our own experience until the exact moment we find ourselves experiencing that all-too-familiar pain of feeling like a stranger in an inexplicable world. Like the prime years for feeling this pain, the movie can be unfocused, dramatic, ostentatious, excessive, superficial, mercurial, and completely convinced of its own special genius. But that doesn’t make its pain any less real, nor does it blunt its gut impact in the end.

Like all of Roeg’s films, it’s a challenging, occasionally excessive work. But it’s inarguably the work of a unique master, and well worth the effort for anyone who appreciates this sort of thing.

Dir. Nicolas Roeg

Starring David Bowie, Rip Torn, Buck Henry, Candy Clark

When a trusted source first recommended Nicolas Roeg's DON'T LOOK NOW by saying it was the scariest movie he had ever seen and had the best sex scene he'd ever seen, I suspected I was about to find a new favorite. I was not disappointed. And yet somehow I never really followed up on Roeg's filmography. Yes, I saw WALKABOUT somewhere, and eventually saw PERFORMANCE (co-directed by even crazier Donald Cammell) but I never undertook the kind of systematic study that Roeg clearly merits from DON'T LOOK NOW alone. In fact, it appears he's made a dozen films on his own, one as recently as 2007. But of course, it was his classic bit of 70s weirdness with David Bowie that first drew my attention, so let's start there.

THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH is called science fiction (

Basically, its kind of fun to enjoy the innocence of a time when someone thought you could get people to take seriously the idea that Bowie's home world looks like a bunch of mannequins wrapped in tin foil living in wigwams with wings in the desert and put that image in the middle of a serious, dark dramatic film.

And you know what? You CAN take it seriously, because the filmmakers are good enough that they convey to you how serious they find it. Their genuine lack of modern cynicism and been-there-done-that weariness is infectious, and makes their ambition to try new things honestly feel way deeper and more effective than would be possible now that we know better. Like those corny scene transitions with the on-and-off cuts in EASY RIDER. Everyone loves that shit about the movie, but has anyone ever tried it in anything else, ever? Of course not, because actually it's pointless, distracting, and ugly. But it’s still fun to watch someone try it so optimistically, so hopeful that they're on to something big.

Anyway, if you can step back and allow yourself to enter a world of 70s hedonistic innocence, the movie is pretty great.

There is a story somewhere in the middle of all the style and narrative experiments --

To

In fact, the whole thing is vague and surreal enough that you might even argue that there's some ambiguity about exactly what's really happening. There’s perhaps enough evidence to suggest that maybe

Ultimately, it’s a film about not being able to go home again – whether you’re E.T. or just a lonely, smart, impossibly thin British weirdo. We’re already so alienated that it takes an actual alien to try and articulate that deep, crushing loneliness seem explicit or worth remarking upon. Roeg has an unusual gift for finding the unseen costs to the soul and making them seem heartbreaking all over again. Here, he cleverly disguises an examination of universal youthful alienation in a story which seems safely removed from our own experience until the exact moment we find ourselves experiencing that all-too-familiar pain of feeling like a stranger in an inexplicable world. Like the prime years for feeling this pain, the movie can be unfocused, dramatic, ostentatious, excessive, superficial, mercurial, and completely convinced of its own special genius. But that doesn’t make its pain any less real, nor does it blunt its gut impact in the end.

Like all of Roeg’s films, it’s a challenging, occasionally excessive work. But it’s inarguably the work of a unique master, and well worth the effort for anyone who appreciates this sort of thing.

Also: [SPOILER] to my knowledge it’s the only 70’s film where two unknown doughy middle-aged guys in business suits show up to put on sparkly gold helmets and throw an old man and his body-building gay partner out a 50th story window. So it has that going for it too.

Friday, May 6, 2011

Helvetica

Helvetica (2007)

dir. Gary Hustwit

The concept of making a full-length documentary about a type face almost seems like a joke -- particularly when you hear that HELVETICA is not some fancy title for a history of printed word or something. The whole film literally is about the Helvetica font. There's a little bit about its history (it was invented in 1957 in Switzerland) at the beginning, but mostly the whole film consists of two things:

1: Interviews with graphic designers who talk a little about their own philosophy, how it relates to Helvetica, and what they think of Helvetica and

2: Musical montages of public signs throughout the world which are set in Helvetica.

That's it, that's all you get. But if that sounds absurdly narrow and dry, the movie has a trick up its sleeve: despite being almost obsessively about Helvetica and Helvetica-related topics, it's not really actually about Helvetica. It's about the evolution of design in the last century, in particular the long running grudge match between modernism and postmodernism.

As they interview more and more graphic artists, a trend slowly emerges. There are some guys extolling the virtues of Helvetica, singing its praises, almost lustfully articulating its perfection. Other guys can barely contain their disgust and compare it to fast food, bureaucracy, and even fascism. At first, there's kind of a cheap thrill in chuckling at these weirdos gnashing their teeth at the proliferation of a type face as if it were a pestilence on the land, but slowly you'll begin to notice that there's something else going on. All the guys who love it are old guys talking about how effective it is, how by communicating clearly and without overt personality it is the ultimate elegant expression of lettering. The guys who hate it are middle age guys who feel that graphic design should be expressive and communicative beyond the content -- that type face has personality which is essential to any kind of meaningful expression of design.

They don't use the words too often, but without directly expressing it they lay out the philosophical history of the art form, merely by putting this one innocuous and ubiquitous type face in front of people who are passionate about what they do, and letting them react to it. It's a nice trick, and it allows the film to benefit from its narrow focus while still speaking to larger and more accessible ideas. Its obsessive interest in this one particular font would be pretty pointless without the subtext about the changing artform, but, curiously, the subtext is also made far more interesting by its unusually limited focus. Helvetica really is the star of the show, and the filmmakers take great pains to remind us just how deeply a part of everyday life this particular type face is. That it goes unnoticed and unremarked on by most of us makes it all the more interesting to have it isolated and placed under the microscope in this manner.

Despite all this, the movie is so stubbornly single-minded that it can drag a little. Most of the interviews are interesting, but they get a little repetitive since there's only so many basic philosophies to articulate and relate Helvetica to. After awhile you get the sense that these guys might have more interesting opinions about other topics, which the film is completely disinterested in exploring. And while the camera's fascination with Helvetica signs nicely adds to the intriguingly zen fixation on Helvetica, they probably don't need to spend minutes on end staring at airport signs to convey the point. The point is a good one, but after experiencing Helvetica fresh after the first few diversions to do this sort of thing, it becomes something akin to the repetition of a mantra and ends up losing all meaning again. They want to be so clear that it ends up muddled and meaningless. The filmmakers might take a hint from designer Dave Carson -- "Don't confuse legibility with communication"

dir. Gary Hustwit

The concept of making a full-length documentary about a type face almost seems like a joke -- particularly when you hear that HELVETICA is not some fancy title for a history of printed word or something. The whole film literally is about the Helvetica font. There's a little bit about its history (it was invented in 1957 in Switzerland) at the beginning, but mostly the whole film consists of two things:

1: Interviews with graphic designers who talk a little about their own philosophy, how it relates to Helvetica, and what they think of Helvetica and

2: Musical montages of public signs throughout the world which are set in Helvetica.

That's it, that's all you get. But if that sounds absurdly narrow and dry, the movie has a trick up its sleeve: despite being almost obsessively about Helvetica and Helvetica-related topics, it's not really actually about Helvetica. It's about the evolution of design in the last century, in particular the long running grudge match between modernism and postmodernism.

As they interview more and more graphic artists, a trend slowly emerges. There are some guys extolling the virtues of Helvetica, singing its praises, almost lustfully articulating its perfection. Other guys can barely contain their disgust and compare it to fast food, bureaucracy, and even fascism. At first, there's kind of a cheap thrill in chuckling at these weirdos gnashing their teeth at the proliferation of a type face as if it were a pestilence on the land, but slowly you'll begin to notice that there's something else going on. All the guys who love it are old guys talking about how effective it is, how by communicating clearly and without overt personality it is the ultimate elegant expression of lettering. The guys who hate it are middle age guys who feel that graphic design should be expressive and communicative beyond the content -- that type face has personality which is essential to any kind of meaningful expression of design.

They don't use the words too often, but without directly expressing it they lay out the philosophical history of the art form, merely by putting this one innocuous and ubiquitous type face in front of people who are passionate about what they do, and letting them react to it. It's a nice trick, and it allows the film to benefit from its narrow focus while still speaking to larger and more accessible ideas. Its obsessive interest in this one particular font would be pretty pointless without the subtext about the changing artform, but, curiously, the subtext is also made far more interesting by its unusually limited focus. Helvetica really is the star of the show, and the filmmakers take great pains to remind us just how deeply a part of everyday life this particular type face is. That it goes unnoticed and unremarked on by most of us makes it all the more interesting to have it isolated and placed under the microscope in this manner.

Despite all this, the movie is so stubbornly single-minded that it can drag a little. Most of the interviews are interesting, but they get a little repetitive since there's only so many basic philosophies to articulate and relate Helvetica to. After awhile you get the sense that these guys might have more interesting opinions about other topics, which the film is completely disinterested in exploring. And while the camera's fascination with Helvetica signs nicely adds to the intriguingly zen fixation on Helvetica, they probably don't need to spend minutes on end staring at airport signs to convey the point. The point is a good one, but after experiencing Helvetica fresh after the first few diversions to do this sort of thing, it becomes something akin to the repetition of a mantra and ends up losing all meaning again. They want to be so clear that it ends up muddled and meaningless. The filmmakers might take a hint from designer Dave Carson -- "Don't confuse legibility with communication"

Thursday, May 5, 2011

Some Thoughts after a few days have passed...

Osama Bin Laden started his career as a man, but by the time he became a household name in the US, he wasn't really a man anymore. An icon, maybe, and idea. The focal point for all our fears, justified or not, about who was an enemy and what they wanted from us. He had a face, he had a history. But somehow it was hard to think of him as a person, an older man sitting out there somewhere in the world, eating lunch, brushing his teeth, typing memos to his underlings. How could we? We saw him only a few short times after that, and we knew nothing at all about his daily life or what he was up to. He was just a name which came to stand for hate, fear, death. I actually assumed that he was already dead, but like any boogeyman we'd never really know for sure.

I expected to hear news reports in 20 years from now ask the question of whatever happened to him. "If he is indeed still alive today," they'd hedge, "he'd be in his 90s, and unlikely age for a man his his condition and his line or work." We'd guess. We'd feel pretty sure. Good intellegence would tell us this or that.

But we wouldn't *know*.

I thought we'd never be able to diminish him to something human again. That he'd gradually merge into the icons of our time. Slowly but surely cease to need any flesh and bones to be our adversary, our albatross.

I think we probably ought to be thanking our lucky starts that things went down this way. It really doesn’t matter exactly how much strategic value Bin Laden had, if killing him would make the world safer, etc. Hell, in all likihood he didn’t even have much to do with the 9/11 attacks directly. But he’s the face that got associated with it, and that was his doing as much as ours. He got what he wanted, which was a decade of America bankrupting itself and banging out head into a brick wall trying to find him; we got what we wanted, which was an easy place to pin the blame for a complex problem. Once we started that narrative there was no way to finish it that didn’t involve one party dead.

Well, now Bin Laden’s dead. We’re not really safer, we expended thousands of lives of trillions of dollars and got involved in a ever-thickening knot of problems which have no solution, and we’ve become a nation of paranoid maniacs all too happy to throw away our comfort, privacy, and rights in chasing some forever-lost sense of security.

We didn’t win. But at least it’s over. And it’s over as cleanly and professionally as it could possibly have been, vastly more so than anything we might have dared hope in this messy, sickening fight against a phantom enemy which changes its own form as often as we change it’s meaning.

It’s not a victory. But it’s a relief. And it’s an opportunity for us to really rethink the things which are important to us and the way we’ve reshaped ourselves and our world. This is something which needed to happen, something unavoidable, and, for once, something definite, something concrete. Bin Laden was a loose end which has been neatly and definatively tied. If ever there was a time to turn a corner and try to put this whole mess behind us instead of digging deeper, it was now.

I truly hope we can seize it.

I expected to hear news reports in 20 years from now ask the question of whatever happened to him. "If he is indeed still alive today," they'd hedge, "he'd be in his 90s, and unlikely age for a man his his condition and his line or work." We'd guess. We'd feel pretty sure. Good intellegence would tell us this or that.

But we wouldn't *know*.

I thought we'd never be able to diminish him to something human again. That he'd gradually merge into the icons of our time. Slowly but surely cease to need any flesh and bones to be our adversary, our albatross.

I think we probably ought to be thanking our lucky starts that things went down this way. It really doesn’t matter exactly how much strategic value Bin Laden had, if killing him would make the world safer, etc. Hell, in all likihood he didn’t even have much to do with the 9/11 attacks directly. But he’s the face that got associated with it, and that was his doing as much as ours. He got what he wanted, which was a decade of America bankrupting itself and banging out head into a brick wall trying to find him; we got what we wanted, which was an easy place to pin the blame for a complex problem. Once we started that narrative there was no way to finish it that didn’t involve one party dead.

Well, now Bin Laden’s dead. We’re not really safer, we expended thousands of lives of trillions of dollars and got involved in a ever-thickening knot of problems which have no solution, and we’ve become a nation of paranoid maniacs all too happy to throw away our comfort, privacy, and rights in chasing some forever-lost sense of security.

We didn’t win. But at least it’s over. And it’s over as cleanly and professionally as it could possibly have been, vastly more so than anything we might have dared hope in this messy, sickening fight against a phantom enemy which changes its own form as often as we change it’s meaning.

It’s not a victory. But it’s a relief. And it’s an opportunity for us to really rethink the things which are important to us and the way we’ve reshaped ourselves and our world. This is something which needed to happen, something unavoidable, and, for once, something definite, something concrete. Bin Laden was a loose end which has been neatly and definatively tied. If ever there was a time to turn a corner and try to put this whole mess behind us instead of digging deeper, it was now.

I truly hope we can seize it.

Hello my name is...

Good Evening. Being a fellow of some opinions which take the form of long-form ramblings, I thought perhaps there would be some benefit for myself and/or mankind in starting a blog where I can put said thoughts and opinions out into the world.

And this is that.

Thank you for your kind attention.

And this is that.

Thank you for your kind attention.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)