|

| (yes, apparently they did this intentionally. I don't know who thought that looked acceptable.) |

Village of the Damned

(1995)

Dir. John Carpenter

Written by David

Himmelstein,

Starring Christopher

Reeve, Thomas Dekker, Lindsey Haun, Kirstie Alley, Linda Kozlowski, Michael

Paré, and Meredith Salenger, but who gives a shit about any of them, because it

also features Mark fucking Hamill as “Reverend George.” That’s right,

you got a John Carpenter movie with God Damn Luke Skywalker in it. And you

haven’t even seen it, you lazy, worthless ingrate. I bet you’ve seen at least

one of those idiot JJ Abrams STAR TREK movies and yet you’ve never even

considered watching this mid-career offering from one of the genre’s

acknowledged masters, even though it stars fucking Mark Hamill. You’re

everything that’s wrong with the world, and it’s time you admitted that.

Another day, another entry into our ever-growing How Could It Not Be Great? canon. Holy shit, you think, John Carpenter, just a year after the

underrated IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS, adapting a novel by the great mid-century

sci-fi author John Wyndham (which had already been adapted into something of a

minor classic in 1960), with a decent budget and a solid cast, how could this

not be… Oh, who am I kidding? You know exactly how this could not be great.

Let’s face it, remaking the 1960 British sci-fi/horror staple VILLAGE OF THE

DAMNED in 1995 was a bad idea from the get-go. The original was deeply and

inseparably a product of its time, drawing its charm from a fragile mix of Cold

War anxiety, mild 60’s British transgressiveness, and stagey (and in

retrospect, more than a little campy) but earnest black-and-white dreamy

matinee creeps.

I am a writer by

avocation, but as a writer about film, I concede to the medium the broad axiom

that “a picture is worth a thousand words.” So consider these three shots to be

the 3,000 or so words it would take me to properly articulate what the 1960

VILLAGE OF THE DAMNED is all about:

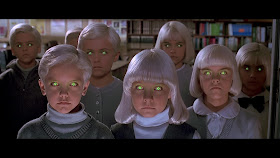

I mean, those three

shots tell you everything you need to know about it, good and bad. On one hand,

there’s no getting around the fact that the little blond kids with glowing eyes

and slack faces are corny as hell. They’re meant to look alien and uncanny, of

course, but the effect is just so artificial and oversold that it’s hard to

take it seriously. On the other hand, the black and white film combined with

the pervading stagey and artificial quality of 50’s British genre cinema (which

this resembles much more than the Hammer-influenced gothic horror explosion of

the 60s) also allows the film to neatly sidestep realism and offer the viewer

at least the option of meeting the film’s signature iconography on its

own terms. Most genre fiction, after all, requires a certain suspension of

disbelief, and in their own native milieu, I think even the glowing-eye

towheads of VILLAGE OF THE DAMNED are a functional object, of sorts.

But let me ask you this,

what if we did the same thing in 1995 in glorious COLOR?

So yeah, this was never going to be a good idea, and, it

should be noted, even Carpenter himself wasn’t too enthused about the project.

As he succinctly put it in a 2011 interview, “I’m really not passionate

about Village of the Damned. I was getting rid of a contractual assignment.”

Which is fair enough, I guess. I mean, a job’s a job, and those Lakers tickets

don’t pay for themselves.

The end result of that contractual assignment is a film

which is hardly in danger of being mistaken for a passion project. It’s

entirely competent -- nothing here suggests the bizarrely misjudged boondoggle

of GHOSTS OF MARS, only six years and two films away -- but it categorically

resists rising to any kind of high point that would give us a clue as to what

someone thought the point was supposed to be. In fact, the plot hews so closely

to the original film that the script by David Himmelstein (a baffling, sparse

resume of four writing credits between 1986-1996, ranging from the Edward James

Olmos sports flick TALENT FOR THE GAMES to Sidney Lumet’s POWER) is credited as

an adaptation of the 1960 screenplay, rather than an adaptation of the 1957

Wyndham novel. It adds a few little details here and there (including a few

touches of gore that seem wildly out of place), but never enough to give any

indication why someone thought this was worth remaking. The eye effects, I

guess? 30 years of special effects progress has finally made it possible to

tell this story the way it was meant to be told… with the same light up

eyes now in COLOR.

Yes, you heard that right. COLOR.

Anyway, the plot is

basically identical to the 1960 version: one day, out of the blue, every living

creature in and around the small California town of Midwich suddenly falls

asleep, wherever they are. Anyone entering the area immediately suffers the

same fate. In six hours, they all awaken, except the ones who were driving, or

tightrope walking, or juggling chainsaws or whatever. Or, in one agreeably gruesome case, standing over a grill. But mostly the citizens just wake up and

go back to their lives, a little unsure what happened. Unsure, that is, until a

few months later, when local doctor Chaffee (Christopher Reeve, in his final

role before an accident left him paralyzed) starts to realize that ten of the town’s women

(including virginal Melanie Roberts, [Meredith Salenger, LAKE PLACID]) seem to

have been impregnated during the “blackout.” And when the kids are born, it

quickly becomes clear that they are some kind of psychic, super-intelligent

hivemind with matching Debbie Harry Sisqo Eminem Machine

Gun Kelly hair and lite-brite eyes. And also that they’re evil.

This last detail is made

clear surprisingly early on, probably the most significant alteration the 1995

script makes. The 1960 version plays out slowly, spending much of its runtime

examining the townsfolks’ strained, confused reaction to this inexplicable

phenomenon and never showing the children doing anything unambiguously hostile

until over 50 minutes into a 77 minute runtime. Here, there’s no doubt; right

from the cradle, these kids are causing mayhem, and pretty much everyone knows

it. On one hand, that was probably the only way to approach this material in

1995; how tedious would it have been to drag it out and try to pretend the

audience doesn’t already know that the creepy little kids with the glowing eyes

are the bad guys? But on the other hand, the entire conflict of the original

film is based on the adults’ wrestling with their uncertainty about what the

kids are, what they want, and what to do with them. Here, all those questions

are answered almost immediately, but the movie doesn’t really pose any

alternate conflict to replace the one it kills off. The two movies proceed

almost identically --even featuring nearly parallel scenes-- except that,

having resolved the central conflict which the 1960 version uses to fuel nearly

its entire plot within the first 20 minutes, the 1995 version finds it has

nowhere to go, and just kind of sits there spinning its wheels, reinforcing the

point over and over that yep, these kids sure are evil, all right. None of it

is bad per se, but it sure is narratively inert, and it really makes you

feel that runtime. Anything under two hours is hardly a difficult ask in this

age where people routinely watch through entire seasons of TV in a single

night, but it’s worth noting that the 1960 version leisurely works through its

storyline in a slim 77 minutes, while Carpenter’s version has arguably less

plot to work through, and still runs a full 22 minutes longer.

Part of that longer

running time --a small part, but a notable one-- is devoted to a smattering of

stepiece kill scenes, which was surely part of the marketing calculous of

bringing Carpenter into the remake. The original has a relatively low body

count --I recall only three victims-- but was certainly not above taking a sadistic pleasure in milking them for morbid thrills. The remake keeps

all three deaths intact, and adds a few more of its own, including a

nasty self-vivisection and a surprisingly huge gun battle (in the original, the

townsfolk consider calling in the military, but dismiss the idea upon realizing

the kids would just use their mind control to make the soldiers shoot each

other. The remake, of course, is understandably curious as to what that would look

like). As with revealing the kid’s malicious intentions early, this makes sense

on the surface, and might in itself have been enough to justify a remake,

if they had really committed to that approach. A pivot from Twilight Zone eeriness

to giddy splatter would be weird, but would certainly embody a fresh approach

to the material, made possible only in the intervening 35 years.

Alas, then, that 1995’s

VILLAGE OF THE DAMNED doesn’t really do that. There’s certainly more explicit

gore than the original, but not nearly enough to give the film a reason for

being, or clearly locate it in a particular mode of horror. It’s appreciated,

but it’s not enough to justify the clash in tones which inevitably results when

you throw five or six gimmicky death scenes into a screenplay essentially

written in 1960. These are two distinct flavors of horror which do not

mesh together comfortably at all. Haphazardly stitching one into the other blurs the film’s focus and heightens the sense of

filmmakers trying to hedge their bets by throwing different things at the

audience to see what sticks, instead of committing to one clear vision.

That same scatterbrained

sense of good ideas indifferently applied carries over into the film’s themes,

too. In the “Production Notes” on the DVD, Reeve reflects, “When they made [the

original] in 1960, the evil alien, if you will, was Communism. This was the

threat, the disease that could overtake this healthy American organism of

liberty and democracy. With the demise of the Cold War, we don’t have that

threat any more. But we have something else -- the indifference to violence.

And the message in this film is the banality of violence, of evil. Death has no

consequence, and metaphorically, we see that here as a kind of infection, which certainly exists in our culture today.”

Maybe so, which helps to

elucidate the decision to portray the kids as blatantly evil right from the

start, and to have pretty much everyone aware of that fact. It’s definitely no

longer a metaphor for a subversion or invasion. But I’m less convinced the

story lends itself well to the idea that it’s about indifference to violence. I

mean, it is about that, I guess, in the sense that the parents spend so

much time begging the kids to feel human emotion and empathy (a point touched

upon in the original, but which is insisted upon here). But it’s not

much of a metaphor since the aliens were just zapped onto Earth, and there’s no

evidence they could be convinced to do anything other than murder us all, and

our only hope is to kill them before they use their telepathic powers to have

us all commit suicide. So what exactly is the message here? “Don’t be a

ultra-powerful psychic sociopath?” OK. I’m not convinced it’s exactly an

immaculate metaphor for creeping Communist menace either, but at least in 1960s

England that threat was understood to come from outside, as an invading

force. Carpenter certainly knows that indifference to violence isn’t some alien

feeling being forced on humanity, it’s an impulse that comes from within us, as

old as civilization, and so representing it with these invading others who

are completely alien and incomprehensible to us just doesn’t really work.

Consequently, the movie offers but doesn’t really commit to this reading,

allowing it, like the setpiece kill scenes, to melt inconsequentially into its

aimless wandering without providing any sense of direction.

Similarly, Carpenter

himself offers a gendered reading of the remake: “The original movie and the

novel were written from a masculine point of view. This was an opportunity to

explore the female aspect of the story and their reaction to the situation.”

I’ll grant the "female aspect of the story" could use some exploring; the 60’s version is so profoundly

disinterested in what the women think that it actually has its protagonist

patronizingly send his wife on vacation while he makes plans to (SPOILER) suicide

bomb their kid. And for a movie which condemns the little monsters for lack

of empathy, its curiosity about the human emotions evoked by this situation

barely extends beyond its mild irritation that emotional women make it hard to

think rationally about the problem. Even original director Wolf Rilla (CAIRO,

and what a name!) agreed that, “We made [our] film at a period when the old

male chauvinism was still very strong. John [Carpenter] has brought another

element into [his film], one of feminism, which is quite right. One discusses

these sorts of things more openly than we did in the 50’s and 60’s, when people

would be uptight about sex and anything to do with it.”

Seems like a good idea,

and there are definitely a bunch of women in the cast, but since none of

these characters are very interesting, and we learn very, very little about

what they’re thinking beyond the most basic platitudes, I don’t know that it

really adds much. Certainly calling it feminist in any sense seems hard

to defend. Maybe it would have been more shocking back in 1995 that the kids

have a female leader (Lindsey Haun, SHROOMS, far and away the most committed

and effective performance in the film), and there’s a cynical female doctor

(Kirstie Alley, STAR TREK 2: THE WRATH OF KHAN and Operating Thetan Level 7)? A

quick survey of contemporary reviews doesn’t give that impression, but what the

hell, good thought, anyway.

Carpenter is also said in the DVD extras to

have added some theological rumination, but man, it’s just barely in

there. I mean, they say bible verses, I guess. But it’s a long way from

exploring the subject in any kind of meaningful way. After all, holy shit!,

aliens and telepathy and mind control! The very existence of these things has

enormous ramifications for our ideas about the soul, about morality, about

death, about humanity’s place in the universe. But all the movie offers is a

grim-looking Mark Hamill (JOHN CARPENTER’S BODY BAGS)

reading a prayer about children. Just another example of how the movie is not

lacking for content, but isn’t really ABOUT anything. It gives the impression

of a film where some thought was put into what to do, but little effort was put

into actually doing it.

Carpenter, even in the

same interview he admits to not caring much about the movie, does claim that,

“it has a very good performance from Christopher Reeve, so there’s some value

in it.” It’d be kind of petty to quibble with something like that, especially

given what happened to poor Reeve afterwords, but although there’s nothing

wrong with his acting, I can’t help but notice that he, like nearly everyone in

the film, is bizarrely miscast. It’s not his fault, really, it’s just that he

is simply not believable as a real human. Come on, nobody is that

ruggedly handsome, he looks like a cartoon prince who shows up at the end of a Disney

movie. The stupid kids in the Sisqo wigs look more convincing. And they are,

after all, kids -- pitting them against a literal superman is a damn

strange dynamic, and having everyone else in the movie try to pretend he’s just

some podunk country doctor and not some kind of adonis übermensch is

even weirder.

The rest of the cast is mostly a wash. Alley is also a

truly befuddling choice for a cynical, vaguely sinister government agent, but

it hardly matters because the role (which has only a tenuous parallel with the

1960 version) is vaguely written in the extreme, with the film unsure how to

posit a character who confusingly vacillates between callused villain and minor

second protagonist. And other than the A+ work from young Lindsey Haun as the

childrens’ leader and spokesman, nobody else in the cast gets much to do. Linda

Kozlowski and Meredith Salenger are both admirably committed to the single

character trait they’re assigned, but can’t do much more. Michael Paré vanishes

before he can leave an impression.

And then you’ve also got

Mark Hamill in there. He’s really trying hard, but unfortunately it’s not much

of a role, and it wouldn’t even really be worth mentioning at all except that

remember, he’s Mark Fucking Hamill, so the fact that he’s standing

around in the background of various scenes making us wish he was talking is kind

of distracting. He plays the town priest, “Reverend George,” in a role which must surely have been meant for an older character actor. In fact, in this

2015 interview he claims he was brought into the production late, after David Warner,

who originally had the part, dropped out. Warner would have been ideal for this

kind of thing (although you’d still be left with a character who isn’t really

given much to do), but Hamill, in 1995, was still too young and pretty to

intuitively read as a fire-and-brimstone small-town country priest, and doesn’t

have enough screen time to convince us with his acting. So it’s just weird.

The strange,

self-defeating casting choices are, in a way, a perfect microcosm of the movie

as a whole. They’re certainly interesting, and even give the impression

that someone, somewhere, was trying to do something, but aren’t nearly

effectively managed enough that you come away with a clear sense of what that

something might be. Even Carpenter’s score (this time co-written with Kinks’

guitarist Dave Davies[!]) seems a little less focused than usual, wandering

between unusually bombastic (but not especially memorable) marches and quiet

minimalism without much sense of purpose.

So in the end, I’m sorry

to have to report that John Carpenter’s VILLAGE OF THE DAMNED is more

interesting curiosity than chilling horror classic. “I had much higher hopes.

The Wolf Rilla one is still the best,” Hamill would later judge. But still, it

is a John Carpenter movie (it has George “Buck” Flowers in it and

everything!), which alone is enough to demand your attention, and fuck, it’s

got goddamn Mark Hamill and Superman going head-to-head against a posse of

murderous alien telekinetic aryan Edgar Winter cosplayer children. Even if it

never quite comes together into the swift kick in the teeth that it should be,

you’d have to be a real asshole not to at least give it a try.

PS: Many reviews point

out that it was filmed at the same sites in Inverness and Point Reyes, CA,

which also appeared in THE FOG. They mention this as though it’s just

interesting trivia, and not hard scientific evidence that Inverness and Point

Reyes, CA, are some kind of filmmaking Kryptonite for John Carpenter.

CHAINSAWNUKAH

2018 CHECKLIST!

Searching For Bloody

Pictures

TAGLINE

|

Beware The Children. So even the tagline is hardly trying.

|

TITLE ACCURACY

|

Has a pretty 1960s

flavor to it, but I guess it’s better than the novel’s title, The Midwich

Cuckoos

|

LITERARY ADAPTATION?

|

Yes, from the 1957

novel The Midwich Cuckoos by John Wyndham

|

SEQUEL?

|

None, although the

1960 version has a sequel called CHILDREN OF THE DAMNED from 1964.

|

REMAKE?

|

Yes

|

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN

|

USA

|

HORROR SUB-GENRE

|

Bad Seed, Psychic

killer, Aliens

|

SLUMMING A-LISTER?

|

Christopher Reeves,

Mark Hamill, Kirstie Alley (I guess?)

|

BELOVED HORROR ICON?

|

John Carpenter

|

NUDITY?

|

None

|

SEXUAL ASSAULT?

|

Women impregnated

against their will, but it seems to be through some kind of outer space

energy ray or something.

|

WHEN ANIMALS ATTACK!

|

In the original, I

remember the dog growls at the evil little kids, though I don’t specifically

remember that happening here.

|

GHOST/ ZOMBIE /

HAUNTED BUILDING?

|

None

|

POSSESSION?

|

Yes, via mind-whammy

|

CREEPY DOLLS?

|

None

|

EVIL CULT?

|

None

|

MADNESS?

|

No

|

TRANSMOGRIFICATION?

|

None

|

VOYEURISM?

|

None

|

MORAL OF THE STORY

|

COMMUNISTS ARE

INFILTRATING OUR CHILDREN AND WE MUST KILL THEM!!!

|

No comments:

Post a Comment