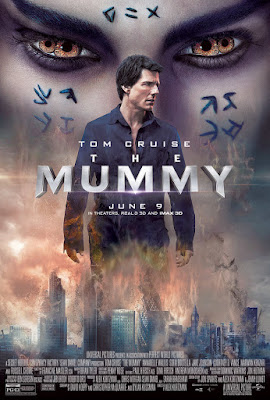

THE MUMMY

(2017)

Dir Alex Kurtzman

Screenplay by

David Koepp, Christopher McQuarrie, Dylan Kussman, Story by Jon Spaihts, Alex

Kurtzman, Jenny Lumet (uh oh)

Starring Tom

Cruise, Annabelle Wallis, Sofia Boutella, Jake Johnson, Russell Crowe.

Let us steel our nerves and consider, for a moment, THE

MUMMY. No, not THE MUMMY (1911), nor THE MUMMY (1932) nor THE MUMMY (1959), nor THE MUMMY (1999), though you’d be forgiven

some confusion. And in fact, I’d wager that confusion is not unintentional;

every Mummy film ever made since the first one has been animated primarily by

the cynical hope of coasting off the good name of another Mummy film and hoping

that vague recognition alone will be enough to inspire good will in audiences.

The whole concept is simulacrum made flesh (and then desiccated and mummified

and revived years later believing that some British blonde is is the reincarnation

of an ancient Egyptian princess, but that’s neither here nor there).

But there has always

been one fatal flaw in that logic: there is no “good name of another

Mummy film.” And that’s because every single extant mummy film is terrible.*

Even the “classic” 1932 Boris Karloff version is, let’s face it, even more

boring than it is racist, and frankly has maintained its iconic standing more

through association with its worthier peers in the Universal Monsters canon

than through any inherent value in the film proper. The Mummy itself --all caps

as a proper noun, for the concept is by this point an intrinsic part of the

American cultural psyche far more than it is a reference to any specific

artistic work-- may well have the singular distinction among the horror icons

of achieving its lofty status without ever at any point actually being

associated with a single film which was any damn good at all. It is, I have

come to believe after an absolutely exhausting survey of Mummy fiction, a trope

which has always owed its entire existence to hustling coattails-riding.

It’s never been good, but somehow it did manage to become familiar,

which in marketing terms is just about the same thing.

With all that in mind, THE MUMMY (2017) starts to make a

little more sense. But even still, only a little more sense. There is, I

guess, a certain sadistic logic in making a new movie called THE MUMMY, in that

it is, you know, a name people would sort of generally recognize and with which

they might perhaps harbor vague positive associations without being able to

explicitly name any concrete reason as to why. In fact, even its ostensible

creators may have had a pretty hazy idea of what, exactly, there were supposed

to be ripping off: it was originally billed as a “reboot of Universal’s ‘Mummy’ Franchise,” though whether

that referred to Universal’s original 1932 Mummy series or Stephen Sommers’

1999 series starring Brendan Fraser was never made clear, and may in fact never

have been explicitly decided one way or another by any of the 60 or so people

who manifestly had a controlling stake in what could generously be called the

“creative process” here. It certainly hews closer to the latter’s mix of corny

action beats and desperate comedy, but really resembles neither in any

meaningful way except through the incidental presence of, you know, a The Mummy.

Which, of course, is the sole reason for its existence in the first place; this

was not a story told because someone had an idea for a story; it was a story

told because someone had to write a story to justify the existence of that

title. But if we must simply remake every single thing that has ever

existed and wormed its way, however undeservedly, into the broader cultural

consciousness, this was inevitable anyway and we might as well have gotten it

out of the way in 2017 as any other time.

So sure, it all makes a

kind of nihilistic sense, radiating a kind of soporific calculation so

inescapable you can basically watch it unfold on-screen in real time. And yet,

even knowing all that, even having written it all down in black and white, I still

can’t quite overcome the unbelievable wrongheadedness of taking a classic

horror icon and trying to fluff it into a huge-budget action franchise vehicle.

I mean, how could anyone ever have thought this was going to work? To the

extent that the Universal Monsters are known at all, it is as clearly and

starkly as horror icons as anything fiction has ever produced. What in

the world would make anyone think they would (or should!) have any salience

outside that context? I get why Universal Studios would want them to (money),

but even at that most cynical, mercenary level, surely someone had to

see that this was hopeless. I can see why they’d want to sell it, but who in

the world did they imagine would actually want to buy it?

Let’s just say what we mean here: this 2017

movie currently enjoying our critical attention exists thoroughly and

unreservedly to fulfill some Universal executive’s dream of having a popular

shared-universe franchise (embarrassingly branded the “Dark Universe”) just

like Disney has with Marvel. And since Universal didn’t buy superheroes,

they’re banking on their stable of classic monster movies to generate the

distasteful but unavoidable “content” necessary for there to be a universe to

share. This is the goal --the entire motivating force behind the

existence of THE MUMMY (2017)-- and the marketing guys have sunk their teeth

into this plan and aren’t gonna let it go til it ain’t moving.

But the thing is, nobody

except Universal executives and their associated marketing teams have ever showed

the slightest bit of interest. They keep starting this thing, failing

spectacularly to find an audience, abandoning it in disorganized, humiliating

defeat, and then inexplicably starting over (the 2004 VAN HELSING debacle, the

2010 WOLFMAN debacle, the 2014 DRACULA UNTOLD debacle, and now this too died at

the box office). But no matter how often it fizzles, they can’t seem to accept

that the problem is in the fundamental idea. All the money in the world can’t

convince people that they want something which has no practical reason to

exist.** Just because something enjoys a wide name-recognition among the

lucrative 18-34 demographic doesn’t mean you can utterly upend its context and

still maintain its original power, no matter how much you might wish otherwise.

And I just can’t imagine any sane writer or director feels otherwise. Nobody

had a burning passion to make this movie any more than anyone had a burning

passion to see it. But in order for it to be marketed, it had to be made, so

here is it. All Hollywood movies are made for crass commercial reason, of

course, but it’s rare indeed to find so many resources being spent to craft a

work of art entirely at the behest of the marketing department.

Well, and at the behest

of Tom Cruise, the only marquee brand here whose name is not THE MUMMY.

In the wake of the movie’s failure, people seem to have been eager to shift the

blame to the actor, who supposedly exerted a huge amount of control over the

finished product, from re-writing the script to supervising the editing. And that seems like a pretty plausible theory;

It’s not at all hard to see some very distinct parallels with the star’s recent

MISSION IMPOSSIBLE and JACK REACHER pictures and their similarly relentless

march of globetrotting nonsense stringing together a parade of mostly-practical

stunt-work setpieces. This sort of wham-bang blockbuster cinema is laughably

out of place in a movie about a Mummy, of course, with its very best sequence

(a legitimately cool uncut take of Cruise and a bunch of stunt-people tossed

around weightless --for real!-- in a crashing plane) having almost nothing to

do with the title character at all. But even if you want to blame the entirety

of the film’s misplaced action-movie ambitions on Cruise, he’d still only be

responsible for one of the three or four completely unrelated movies

vying for supremacy during the film’s unexpectedly demure 110-minute runtime

(practically a short film by the standards of modern blockbusters). And it’s by

no means the worst of them.

Those four unrelated

movies are as follows, in descending order of tolerability: A mummy movie, an

action vehicle, a prequel to a mummy movie, and a labored franchise-servicing

purgatory starring Russell Crowe. All are bad in their own way, of course, but

some are rather more exotically dismal than others. In the first of

these movies, a couple of incessantly quipping mooks --Cruise (AUSTIN POWERS IN

GOLDMEMBER), Annabelle Wallis (ANNABELLE [and niece of Richard Harris!]) and

Jake Johnson (that smarmy millenial fuck-o from JURASSIC WORLD***) find a --hey! what have we here?-- mummy’s

tomb [!] due to some sort of convoluted horseshit about the US military in

Iraq,**** and get themselves cursed in the process. Standard mummy stuff, but

made tolerable by its likable cast, by-the-book plotting, and surprising

deftness for horror staging. You’ll notice, in fact, that this simple premise

would be comfortably sufficient to fill out an entire movie. But this is

a big studio blockbuster in the year of our Lord 2017, so “enough” is, of

course, never enough until it’s “far too much.” And thus we get three

additional movies competing with the only one which has any real legitimate

reason to exist.

The second movie is some kind of

setpiece blockbuster doggedly committed to hurling frantic stunt sequences at

us every now and again, and mostly indifferent to the fact that it’s about a

The Mummy or whatever. These sequences are pretty middling by Crusie’s usual

standards, but the plane crash bit is a winner, and there’s even a rambling

chase sequence that occasionally remembers that it’s in a horror movie and uses

its mammoth budget to give us some enjoyable zombie mayhem which you could

never get in a movie with a normal zombie budget, so not a total wash. Third,

we have, intermittently, the story and --ominously, as longtime Mummywatchers

are all too aware-- the backstory of the title character (Sofia

Boutella, CLIMAX). Supposedly this was once a more prominent part of the movie,

as in the final product Boutella has almost nothing to do but stand around

looking menacing and flash back to the origins of her Mummying in a rather

wearying repetitive manner. Here we might actually be able to thank Cruise for

jealously excising his co-star’s tiresome life story from the final cut,

because this is, of course, utterly dire stuff. Still, it’s a venerable and

--more to the point-- inescapable part of the basic Mummy movie

boilerplate, so we could hardly be surprised that it remains, even in the year

2017, an inconvenience that veteran connoisseurs of mummy fiction expect and

resign themselves to endure.

The final movie,

though, is something wholly unexpected. This is because, crudely sutured into

this thoroughly quotidian paint-by-numbers Mummy Movie yarn, we find something

exponentially weirder, a subplot about a secret society of monster hunters

which feels like the jarring intrusion of a completely separate movie, because

that’s in fact what it is: the covetous tendrils of the “Dark Universe”

creeping their way into a unambitious self-contained little thriller to force

the world, against its better judgement, to acknowledge the existence of a

shared universe which does not, by God, actually exist yet, and may never exist.

And thus it is that before we meet a single character who will actually be

germaine to this particular tale, we encounter one Dr. Henry Jekyll*****

(Russell Crowe, NOAH) owner and operator of a monster-hunting

franchise called “Prodigium” which appears to be quite a lucrative venture

judging from their expansive, well-appointed headquarters with enough

jumpsuit-sporting henchmen and technological goo-gahs to handily pass for a

Bond Villain’s lair.

Crowe is, for whatever

reason (possibly alcohol-related), obviously having a ball hamming up a

performance which consists wholly and without exception of tedious

exposition, most of it necessary only to explain his own incongruous presence

in this mummy movie. He’s clearly decided that the only possible means of

survival is to turn the thing into some kind of high camp parody of a

terribly-written exposition-spewing non-character crammed into a movie that has

neither need or space for him, entirely in a labored effort towards servicing a

franchise which may never actually exist. But while this is obviously the

correct approach, and does something to render this little sub-movie

slightly short of instantly lethal, everything about this plotline is useless

and burdensome and completely stops the movie dead in its tracks, efficiently

euthanizing any lingering bits of momentum that might have been building up

while the creative team wasn’t paying attention. Without it, THE MUMMY 2017

would simply be unfocused mediocrity; with it, it becomes something

closer to a genuine boondoggle, something which will seem absolutely

confounding to a hypothetical future audience who does not have the proper

context to understand why there’s a 30-minute teaser commercial for a

non-existent franchise jammed into the back half of an otherwise stock mummy

flick.

In a way, a spectacular

disaster is a more interesting thing to have in the world than a middling

studio flick too unimaginative to embarrass itself in any noteworthy way, which

passes unremarked upon through cinemas and promptly vanishes from human memory.

But you know, there are moments -- and only moments, to be sure-- where

one wonders if perhaps “middling mediocrity” and “staggering folly” weren’t the

only two possible outcomes here, if there

wasn’t an actual good movie to be found here, if only someone had stopped to

notice it. Those moments have little to do with Tom Cruise stunts --which are

found in profusion, and in rather more colorful array, in other movies better

suited to their charms-- and are certainly never found in the enervating mummy

backstory or even in the disposable clutter or the basic plot. Where they are

found is the only real surprise in the whole film, because they turn up in

the one place the movie seems least interested: its mostly-forgotten origins as

a horror movie.

For whatever reason

(craftsman’s pride, perhaps, or simple boredom, but surely not a deep sense of

belief in the project’s artistic merit) “creature designer” Mark 'Crash'

McCreery (JURASSIC PARK, LADY IN THE WATER) actually designed some pretty

great-looking reanimated corpses which make full use of the film’s indefensible

budget to offer us a range of impossible herky-jerky movements and imaginative

demises that are simply out of reach for horror films that don’t employ an army

of visual effects artists. I also very much like the double-iris eyes which makes for the film's most striking visual. Most important, though, THE MUMMY 2017 offers something

that almost no other Mummy film has so far been able to convincingly produce: a

skinny, desiccated, unwrapped mummy lurching around on brittle bones like a

malevolent spider on the hunt. It looks, in other words, like a genuine

mummified corpse, not like some beefy guy wrapped in toilet paper, a

distinction which lends it an unexpected visual potency despite its

familiarity.

The image of a spindly, half-skeletal ghoul

has actually been part of Mummy fiction for quite some time; Arthur Conan

Doyle’s 1892 gothic classic Lot No. 249 --which comprises, along with

Bram Stoker’s 1903 Jewel Of The Seven Stars, the baseline popular origin

of the genre******-- describes just such a creature, which would have, in fact,

likely been more familiar to the Victorian Egyptophiles of his time (who

delighted in “mummy unwrapping parties” -- a pass-time only slightly less morbid than today's "unboxing videos" ) than the bandage-swaddled version which has

since become the standard iteration of the concept (and certainly saw its

high-water mark with Christopher Lee’s imposingly buffness in Hammer’s 1959 THE MUMMY). McCreery, cinematographer Ben Seresin (PAIN

AND GAIN) and director Alex Kurtzman (first-time director,******* but long-time

bane of screenwriting as part of the dreaded Orci/Kurtzman duo) make the most

of the exotic design by highlighting its boney, impossible movements against

--why, what have we here?-- gothic swirling mists in an old abandoned

churchyard! Holy shit, it’s almost like this was the correct context for a

century-old horror icon all along! Who woulda thunk it?

It’s a trivial thing, of

course, in the face of so very much howling sound and fury signifying nothing,

but it’s also a frustrating glimpse of the simple pleasures which were right at

the filmmakers’ fingertips, had they bothered to notice them. For all the

miserable, inept mummy movies that have been made (and they’re all miserable

an inept), there is something about this concept that has continued to

stir the imagination of generations of horror fans. At a particularly low point

in my journey through mummy fiction, I lamented that a mummy

is basically just a solitary zombie that can’t bite you, and maybe we ought to

admit it simply isn’t a cinematic concept worthy of much more exploration. But

that’s not really true; or anyway, not entirely true, though it’s

certainly a fitting complaint for virtually every single iteration of the

concept I’ve ever seen on screen.

Fundamentally, a

reanimated mummy should (or could, at least) have a little more

resonance than that. A mummy doesn’t just traffic in our discomfort with dead

bodies and the appalling wrongness of their return to some sort of unnatural

half-life (though of course it does this too, and with a unique tactile quality

perhaps better embodied in this movie than any other, of a body not rotting or

mutilated, but rather desiccated, drained of its vital fluids in an uncanny

parody of preserving vitality). More than our fear of dead things, it traffics

in an almost Lovecraftian sense of unknowable antiquity reaching into the

present in unanticipated, incomprehensible ways.******** Very nearly 200 years

after Jane C. Loudoun published The Mummy!: Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second

Century (the earliest tale of a reanimated mummy that I can identify) our

knowledge of the ancient Egyptian culture has grown exponentially, but it still

maintains its ability to mystify and intrigue us, as evidenced by its integral

place in the essential folklore of our time, from conspiracy theories to ancient

alien hypotheses. For all our technological progress, we are still awed and

humbled by the scale and permanence of what they achieved, and the level of

sophistication they reached literally thousands of years before our time.

A mummy, then, is less a

metaphor for our fears of death and loss of personal identity than it is a

cultural avatar from a forgotten past, challenging our smug certainty that we

are the unquestioned masters of creation. In a chapter of Jewel Of The Seven

Stars which he deleted from subsequent editions, Stoker actually makes this

point explicit: if, in fact, the central mummy succeeds in using the unknown

magic of antiquity to revive itself, the staunch Englishmen don’t just lose a

battle, they lose their very sense of identity. Their belief in the essential

correctness of their culture, religion, and basic understanding of the

mechanics of the universe, get swept away into a terrifying chaos of

uncertainty. This, I think, is the key to The Mummy’s persistence as a iconic

figure despite a century of dull film iterations; at its core, the Mummy

symbolically challenges not only the frailty of human life, but the fragility

and vulnerability of our most fundamental assumptions about ourselves and the

world. It is an alien, an other, emerging from a world out of time, a

world utterly unfamiliar and remote but so manifestly remarkable that its very

existence is a challenge to our innate sense of superiority. If the mummy bests

us, we’re not just in physical danger, we’re existentially at risk of being

forced to relinquish our place as the arbiter of civilization to its rightful

heir.

All this was right

there for the makers of this film, which had every conceivable resource to

realize these themes if any film ever put to (digital) celluloid could ever be

so described. And the most infuriating thing is that the ingredients are all

unmistakably there; the film has a great sense of the disturbing corporeal

wrongness of the mummy’s reanimated remains (when the filmmakers bother to try

for it), and even adopts Stoker’s essential structure of a possession tale,

personalizing the basic metaphor of culture being supplanted by the malevolent

manifestation of the ancient primordial past. Hell, it even goes one step

further and adds the unnecessary but intriguing detail that this is the product

of imperial overreach: for the Victorian and Edwardian Brits presiding over an

uneasy globe-straddling empire, anxieties that the “natives are restless” found

outlets in the “Imperial Gothic” tales of the time which provided the fertile soil from which

sprung the origins of mummy fiction. But in 2017’s THE MUMMY, we find the

inciting incident to be the product of a different type of colonizer: a US

soldier looting native treasures in American-occupied Iraq. It’s almost enough

to tempt one to wonder if someone here, writing some far-removed early

version of the script from which these tiny vestigial details were retained

even absent their original significance --as a dozen more writers brazenly

re-shaped the tortured mass into new and ever more contorted convolutions--

knew what they were doing. But probably they just happened to blindly snare a

couple key ideas in their brute trawl of every possible cliche their

predecessors had yet devised.*********

So it has the right

ingredients to actually make something of its premise, though hopelessly mixed

into a haphazard, overflowing pile of unrelated and contradictory detritus. As

I have admonished so many times in the past, however, ingredients are not a

meal. And it will come as no surprise to you that despite these potentially

salient elements being present at various points in the plot, the movie makes

absolutely not the slightest thing of any of them.The uniqueness and majesty of

Ancient Egypt, in particular, is woefully neglected; though we do get some

requisite flashbacks, the Egypt our antagonist occupies is a bland, undefined

space, filled mostly with medium-sized candle-lit rooms which are furnished

almost exclusively with billowing curtains (which actually seems like kind of a

fire hazard, but I guess you worry a lot less about that in houses built of

giant limestone and granite slabs). With the exception of name-checking

notorious Egyptian heel-god Set (sometimes also called Seth), “Princess

Ahmanet” might as well be a villainous witch from any time and place in

history, or, perhaps more likely, from no specific time and place at all. And

if it can’t even be bothered to engage with the one essential element of its

own basic premise, you can hardly expect it to do any better with the more

tangential elements: The film abandons its promising horror imagery almost as

quickly as it stumbles upon it, and shrinks away from its provocative Iraqi war

elements with a pronounced discomfort which is almost palpable.

Which is, I realize, not

telling you anything you don’t already know. 2017’s THE MUMMY is dumb and bad,

just like all mummy movies are dumb and bad, which was already so obvious to

you that you’ve never even considered seeing this piece of crap and have only

read this far into this review in the vain hopes of trying to understand why I

would so unwisely do so. And yes, it’s dumb and bad. But I’m sorry to say

you’re going to have to see it anyway, and I’ll tell you why: for reasons too

pointless to get into, the action eventually moves to a secret crypt hidden

under London’s subway system, where the bodies of returned crusaders have been

interred. And what does the Mummy do when she arrives? Why, raises the departed

knights from their tomb, of course. And just like her, they’re ancient,

eyeless, desiccated corpses still wearing the symbols of the ancient Templar

order to which they belonged. You see where I’m going with this? Undead,

eyeless Templars! This is basically the fifth BLIND DEAD movie!********** And at one point Tom Cruise

punches one of them and gets his hand stuck in his ribcage! So it’s not all bad

news. In fact, compared with the rest of the BLIND DEAD movies, this is

probably one of the two or three best! As both reanimated mummies and the

filmmakers behind the venerably lowbrow subgrene of Mummy fiction almost always

eventually discover, context really is everything.

FIN

* THE MUMMY (1911), being a lost film and

therefore unseen my me, is a possible exception, though the plot synopsis does not exactly inspire confidence.

** Or anyway, can’t always do it;

that the BEAUTY AND THE BEAST remake from 2017 grossed over a billion dollars

provides ample evidence that it certainly can be done, and also also as

a bonus definitively proves that there is no God and we live in a cold,

indifferent amoral universe where ‘justice’ and ‘right’ are empty, meaningless

abstractions which crumble like dry leaves before the might of Lord C’thulhu.

*** He did play “Jesus Christ” in A VERY HAROLD

AND KUMAR 3D CHRISTMAS, though, so I can’t be too mad at him.

**** A weirdly tone-deaf plot device by any

metric, and made even weirder by its absolute needlessness and total

irrelevance to the rest of the so-called story.

***** Dr. Jekyll, of course, was never part of

the Universal Horror canon (there was a 1931 Paramount version with Fredric

March and a 1941 MGM version with Spencer Tracy) though, as with VAN HELSING,

Universal Executives seem absolutely convinced to the contrary. Perhaps they’re

getting confused by the existence of 1953’s ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET DR. JEKYLL

AND MR. HYDE, as near as I can tell the only classic Universal production to

ever include the character? But if meeting Abbott and Costello is all it takes

to be considered a iconic Universal Monster, the Keystone Kops may also turn up

in the “Dark Universe.”

****** Of course, we can trace the lineage back

further than that, as I intend to do in my forthcoming book-length A

Cultural Anthropology of the Mummy. But for today’s purposes, I think it’s

fair to call those two stories the basis of the modern conception of “The

Mummy” as a distinct boogeyman of the horror genre. (Bonus trivia: Louisa May

Alcott, of Little Women fame, wrote a very early “Mummy’s Curse” story

called Lost in a Pyramid; or, The Mummy's Curse in 1869, decades before

either Doyle or Stoker. It does not, however, feature a resurrected, ambulatory

mummy seeking revenge)

******* And why not hire a first-time

director for a huge franchise-inaugurating iteration of an iconic screen

classic with a budget of $200 million?

******** Indeed, Lovecraft himself wrote (or

co-wrote/ghost-wrote, with Hazel Heald) a mummy story of his own: 1935’s Out

of the Aeons. Of course, Lovecraft was racist enough that he damn sure

wasn’t going to situate a great lost civilization in Africa, so it’s a mummy

from the lost continent of Mu. But we know damn well where mummies come from,

Howard. UPDATE: As commenter Matthew points out, Lovecraft too knew where mummies come from; early in his career, he ghostwrote a story called Imprisoned With The Pharaohs (1924) for none other than Harry Houdini.

********* A quest which also snared, I might

add, some decidedly non-mummy related fiction; how else do we explain the

brazen daylight robbery of several specific plot elements and even scenes from

AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON? Did one of the writers misread the memo and

start watching werewolf movies before someone corrected him about the genre he

was supposed to be ripping off?

********** Or sixth, if you want to count the other

unofficial BLIND DEAD sequel, John Gilling’s 1975 La cruz del diablo.***********

*********** By the way, I want to point out that

that tenth footnote marks a decisive record for most ever footnotes on a single

piece I’ve written! Thanks, THE MUMMY!

SHAMELESS PLUG: If you enjoy my thoughts on cinema, you can also follow me on Letterboxd, where I post shorter-form reviews of a wider range of films.

SHAMELESS PLUG: If you enjoy my thoughts on cinema, you can also follow me on Letterboxd, where I post shorter-form reviews of a wider range of films.